For most people, the inability to fall asleep is caused by Psychophysiological Hyperarousal.

Essentially, your nervous system is stuck in “Fight or Flight” mode due to a misalignment of two hormones: Cortisol (stress hormone is too high at night) and Melatonin (sleep hormone is too low). This prevents the brain from switching off, even when your body is exhausted.

If you lie in bed exhausted but unable to fall asleep, your sympathetic nervous system is likely still activated when it should be shutting down. This physiological hyperarousal — characterized by elevated cortisol, increased heart rate, racing thoughts, and muscle tension — prevents the transition into sleep even when you’re physically tired.

Stress activates your body’s fight-or-flight response, raising cortisol levels that should naturally decline in the evening. Modern life compounds this through chronic stress, evening screen exposure, late caffeine intake, and insufficient decompression time between daily demands and bedtime. Your brain interprets these signals as threats requiring alertness, making sleep initiation physiologically impossible.

The inability to fall asleep isn’t a willpower problem or “bad at sleeping” — it’s a nervous system regulation issue. Understanding what keeps your brain alert when it should be winding down is the first step toward actually fixing it.

Want Better Sleep Stats?

Theory is good, but tools get results. See the exact stack (mask, tape, supplements) I use to get 2+ hours of Deep Sleep every night.

Open Sleep HubThe Frustrating Reality of Sleep Onset Insomnia

You’re lying in bed, physically exhausted. You’ve been awake for 16+ hours. Your body is tired. Your eyes are heavy. But your brain won’t shut off. You’re aware of every sound, every sensation, every random thought. Twenty minutes pass. Then forty. Then an hour.

You start doing math: “If I fall asleep RIGHT NOW, I’ll get 6 hours… 5.5 hours… 5 hours…” The calculation itself becomes another source of stress. You try everything — changing positions, adjusting pillows, taking deep breaths, counting backwards. Nothing works. Your frustration builds, which makes sleep even more elusive.

This is sleep onset insomnia, and it’s one of the most common sleep complaints. Unlike sleep maintenance insomnia (waking during the night) or early morning awakening, sleep onset insomnia specifically means you can’t transition from wake to sleep despite being tired.

Why “Just Relax” Doesn’t Work

Everyone who’s struggled with sleep onset has received this unhelpful advice: “Just relax and you’ll fall asleep.” If it were that simple, you would have done it already.

The problem is that falling asleep isn’t a voluntary action. You can’t force yourself to sleep through willpower any more than you can force yourself to digest food faster or lower your blood pressure through concentration. Sleep is a biological process that requires specific physiological conditions.

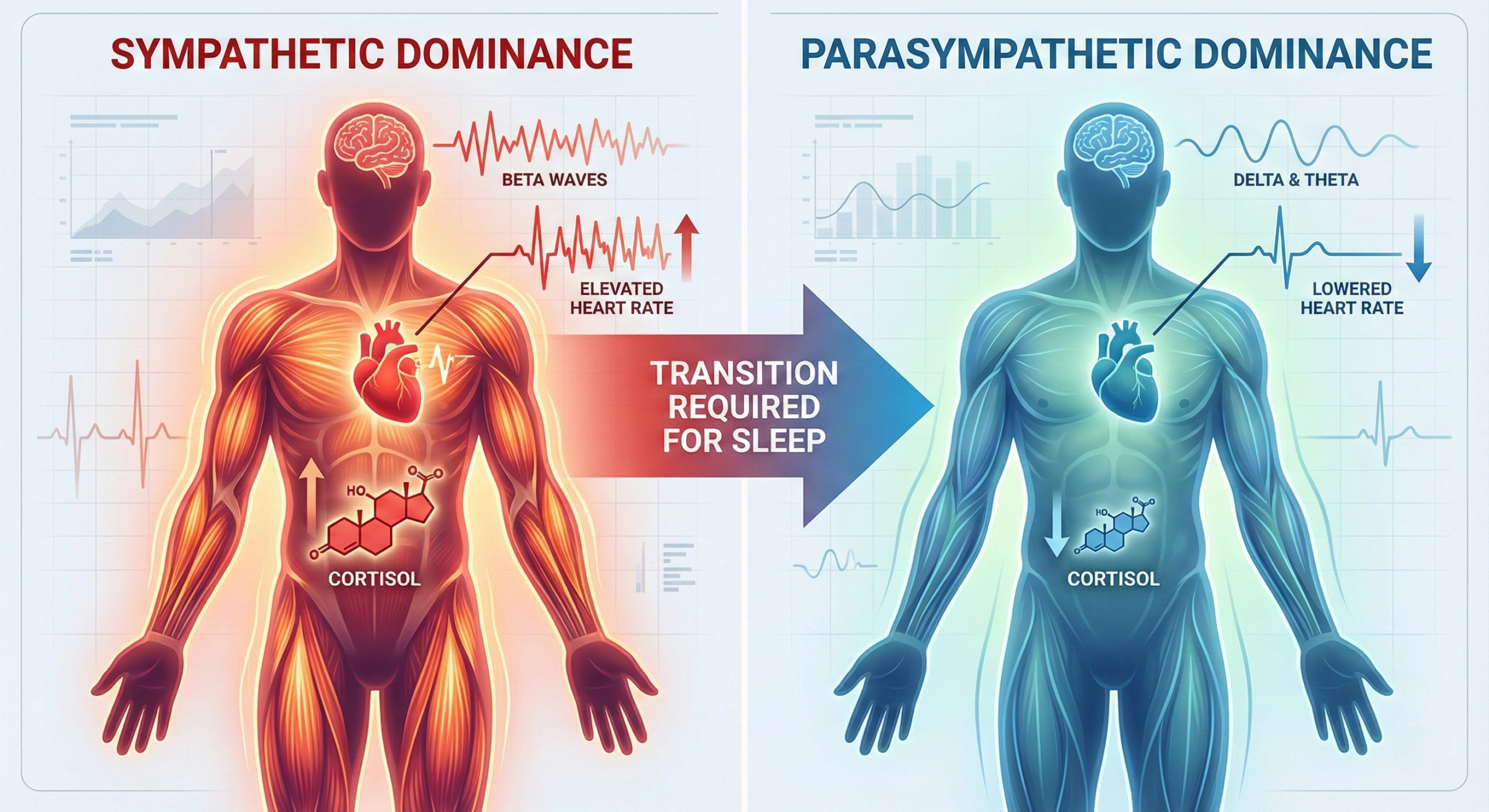

What needs to happen for sleep to occur:

- Sympathetic nervous system activity decreases (fight-or-flight system turns off)

- Parasympathetic nervous system activity increases (rest-and-digest system turns on)

- Cortisol levels drop below a threshold that permits sleep

- Core body temperature declines

- Adenosine (sleep pressure) reaches sufficient levels

- Melatonin rises in the absence of alerting signals

- Brain shifts from beta/gamma waves (alert) toward alpha/theta waves (drowsy)

When any of these conditions aren’t met — particularly sympathetic activation remaining high — sleep initiation is physiologically impossible. You’re lying in bed exhausted but your body is in a state that says “stay alert.”

My experience: I spent years thinking I was “bad at sleeping.” I’d lie in bed for 60-90 minutes nightly, frustrated and confused about why I couldn’t just “turn off” despite being exhausted. I’d try meditation, breathing exercises, progressive muscle relaxation — sometimes they’d help marginally, but nothing consistently worked.

It wasn’t until I understood that my sympathetic nervous system was still activated (elevated heart rate variability measurements confirmed this) that I realized the problem wasn’t psychological resistance to sleep — it was physiological arousal preventing the transition. My body was literally not in a state that allowed sleep initiation.

The Vicious Cycle of Performance Anxiety

Once you’ve experienced several nights of lying awake unable to fall asleep, a new problem develops: anticipatory anxiety about sleep itself.

The anxiety-insomnia cycle:

- You have trouble falling asleep (initial cause: stress, overstimulation, etc.)

- You become worried about your ability to sleep

- Approaching bedtime triggers anxiety (“What if I can’t sleep again?”)

- The anxiety itself activates your sympathetic nervous system

- The physiological arousal makes sleep impossible

- This confirms your fear, strengthening the association between bed and wakefulness

- The pattern repeats, often worsening over time

Research on insomnia demonstrates that chronic insomnia often begins with an acute stressor but persists long after the stressor resolves due to conditioned arousal and maladaptive sleep behaviors.

How this manifests:

- You feel fine during the day, but as bedtime approaches, anxiety rises

- Getting into bed triggers immediate alertness rather than drowsiness

- Your bedroom becomes associated with wakefulness and frustration rather than sleep

- You start avoiding bed, staying up later, or sleeping elsewhere (couch, chair)

- The problem compounds as sleep deprivation increases overall stress

I developed this pattern severely. Around 8-9 PM, I’d feel a knot in my stomach thinking about bedtime. By the time I got into bed, my heart rate would increase 10-15 bpm just from the association between bed and sleeplessness. The bedroom itself had become a trigger for arousal.

Breaking this cycle required addressing both the physiological hyperarousal (the root cause) and the conditioned anxiety (the maintaining factor).

How Stress Activates Your Fight-or-Flight Response (And Keeps You Awake)

To understand why stress prevents sleep, you need to understand your autonomic nervous system — the part of your nervous system that controls involuntary functions like heart rate, breathing, digestion, and arousal state.

The Two Branches — Sympathetic vs Parasympathetic

Your autonomic nervous system has two branches that generally work in opposition:

Sympathetic nervous system (SNS) — “Fight or flight”

- Activated by stress, threat, excitement, or stimulation

- Increases heart rate and blood pressure

- Dilates pupils

- Redirects blood flow to muscles

- Increases respiration rate

- Releases stress hormones (cortisol, adrenaline)

- Suppresses digestion

- Creates alertness and vigilance

- Prevents sleep initiation

Parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) — “Rest and digest”

- Activated during relaxation, safety, and recovery

- Decreases heart rate and blood pressure

- Constricts pupils

- Redirects blood flow to digestive organs

- Slows breathing

- Reduces stress hormone levels

- Promotes digestion

- Facilitates recovery and restoration

- Permits sleep initiation

For sleep to occur, you need parasympathetic dominance. When sympathetic activity remains elevated, sleep is physiologically blocked regardless of how tired you are.

Studies using heart rate variability (HRV) as a marker of autonomic balance show that individuals with insomnia exhibit higher sympathetic tone and lower parasympathetic tone both during the day and at night compared to good sleepers.

What Activates the Sympathetic Nervous System

Acute stressors (immediate threats):

- Work deadlines, conflicts, difficult conversations

- Financial stress, relationship problems

- Physical danger or perceived threats

- Intense exercise

- Caffeine and other stimulants

- Bright light (especially blue light wavelengths)

Chronic stressors (ongoing background stress):

- Job insecurity or toxic work environment

- Caregiving responsibilities

- Chronic health issues

- Financial instability

- Social isolation or relationship dysfunction

- Perfectionism and high self-imposed demands

Research on chronic stress and sleep found that individuals experiencing chronic life stress show persistently elevated evening cortisol and reduced sleep quality, with the relationship partially mediated by hyperarousal and rumination.

Modern overstimulation (ambient activation):

- Constant digital connectivity (notifications, emails, texts)

- Information overload (news, social media, endless content)

- Environmental noise (traffic, neighbors, household sounds)

- Blue light exposure from screens in evening

- Lack of genuine downtime or mental decompression

What’s particularly insidious about modern life is the constant low-level sympathetic activation. You’re not experiencing acute fight-or-flight stress, but your baseline arousal never fully drops to parasympathetic dominance. You’re chronically shifted toward sympathetic tone.

My stress profile when I had severe sleep onset problems:

- Checking work email until 9-10 PM

- News/social media scrolling until bedtime

- Apartment in noisy urban area (ambient sirens, traffic)

- Caffeine consumption until 2-3 PM (half-life meant it was still active at bedtime)

- No transition period between “work mode” and “sleep mode”

- High-stress job with frequent evening calls

I was essentially maintaining sympathetic activation from 7 AM until I attempted sleep at 11 PM, then wondering why I couldn’t fall asleep. My nervous system had no opportunity to shift into parasympathetic dominance.

Why Evening Stress Is Particularly Problematic

Stress at any time of day affects overall health, but evening stress is especially damaging to sleep because it occurs during the critical wind-down period when your body should be transitioning toward sleep readiness.

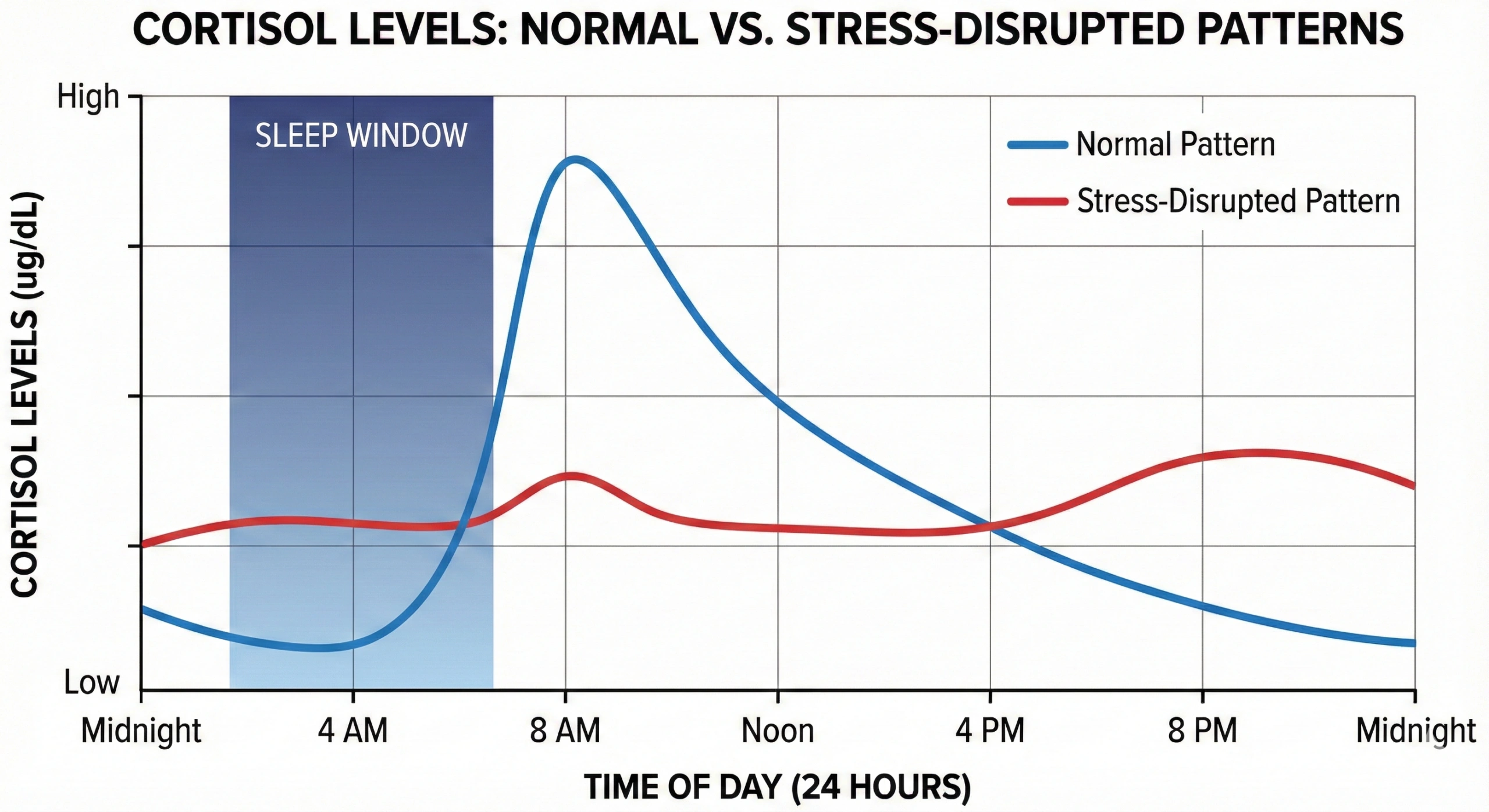

The evening cortisol problem:

Cortisol naturally follows a circadian rhythm:

- Peak: 30-45 minutes after waking (cortisol awakening response)

- Gradual decline throughout the day

- Nadir: Around midnight to 2 AM

- Begins rising again around 3-4 AM

For healthy sleep, you need cortisol to be declining in the evening. Evening stressors cause cortisol spikes at exactly the wrong time.

Studies measuring evening cortisol in people with insomnia found that sleep onset insomnia correlates with elevated cortisol in the evening and early night, particularly in the hours before attempted sleep.

Common evening stressors:

- Work extending into evening (emails, calls, projects)

- Intense or stimulating media (action movies, disturbing news, heated social media debates)

- Difficult conversations with partners or family

- Evening exercise that’s too intense or too close to bedtime

- Financial stress (paying bills, checking accounts)

- Planning/worrying about next day

Each of these triggers a cortisol response that can persist for 1-3 hours, preventing the natural evening cortisol decline needed for sleep.

My worst habit: I’d check work email at 9:30-10 PM “just to see if anything urgent came up.” Inevitably, there’d be something that triggered stress — a demanding client, a problem that needed solving, a passive-aggressive message. My cortisol would spike, and I’d lie in bed 45 minutes later unable to sleep, mind racing about work issues.

Once I created a hard cutoff (no work email after 7 PM), my sleep onset improved within a week. The correlation was undeniable.

| If You Feel Like This… | The Likely Biological Cause | Immediate Fix |

|---|---|---|

| “Tired but Wired” (Exhausted body, racing mind) | High Evening Cortisol. Your stress hormone failed to drop, keeping your brain alert. | Lower body temp (cool shower) + Box Breathing technique. |

| Waking up at 2-3 AM (Sudden alertness) | Blood Sugar Crash. Your body released adrenaline to stabilize glucose levels. | Eat a small snack before bed (raw honey or collagen). |

| Can’t shut off thoughts (Anxiety loops) | Psychological Hyperarousal. Your brain interprets bedtime as a “threat” or problem to solve. | “Brain Dump” journaling 1 hour before bed to clear RAM. |

| Not tired until 2 AM (Night owl) | Delayed Circadian Rhythm. Your internal clock is shifted late. | View morning sunlight (10-20 min) + No blue light after 9 PM. |

Understanding Cortisol’s Role in Sleep Disruption

Cortisol is often called the “stress hormone,” but it’s more accurately described as your body’s arousal and alertness hormone. While acute cortisol elevation is adaptive (it helps you respond to threats), chronically elevated or poorly-timed cortisol directly interferes with sleep.

What Cortisol Does to Your Body

Cortisol is released by your adrenal glands in response to signals from your hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. It serves multiple functions:

Beneficial cortisol functions (when properly timed):

- Increases glucose availability for energy

- Enhances alertness and focus

- Mobilizes resources for dealing with stressors

- Regulates immune function

- Helps you wake up in the morning (cortisol awakening response)

Problematic cortisol effects (when elevated at night):

- Increases heart rate and blood pressure

- Promotes glucose release (raising blood sugar when you should be fasting)

- Antagonizes melatonin (suppresses your sleep hormone)

- Increases core body temperature (opposite of what’s needed for sleep)

- Maintains alertness and vigilance

- Keeps sympathetic nervous system activated

- Directly blocks sleep initiation

Research on cortisol timing and sleep shows that even modest evening cortisol elevations correlate with increased sleep onset latency and reduced sleep efficiency.

The cortisol-melatonin antagonism:

Cortisol and melatonin have an inverse relationship. When cortisol is high, melatonin secretion is suppressed. Since melatonin needs to rise in the evening for sleep onset, elevated cortisol directly prevents this from happening.

Studies demonstrate that cortisol levels above certain thresholds can suppress melatonin production by 50-70%, even in darkness.

This is why stress-induced cortisol elevation is so damaging to sleep — it’s not just keeping you alert, it’s actively preventing the hormonal shift (melatonin rise) needed for sleep initiation.

What Causes Evening Cortisol Elevation

Psychological stress:

- Worrying, rumination, anticipatory anxiety

- Unresolved conflicts or problems

- Perfectionism and self-criticism

- Work stress extending into evening

Physiological stressors:

- Late-day caffeine (triggers cortisol release)

- Intense exercise within 3 hours of bedtime

- Large meals close to bedtime (metabolic activation)

- Pain or physical discomfort

- Sleep deprivation itself (creates vicious cycle)

Circadian misalignment:

- Late light exposure (blue light from screens)

- Inconsistent sleep schedules

- Shift work or jet lag

Blood sugar dysregulation:

- Evening hypoglycemia (low blood sugar triggers cortisol)

- High-glycemic meals causing insulin spike followed by crash

- Skipping dinner or eating too early

Each of these triggers can raise cortisol at exactly the wrong time, preventing the natural evening decline.

The Chronic Stress Problem

Acute stress causes a normal cortisol spike that resolves within hours. Chronic stress dysregulates the entire HPA axis, leading to abnormal cortisol patterns.

Healthy cortisol pattern:

- Strong morning peak

- Steady decline throughout day

- Low evening levels

- Nadir around midnight

Chronic stress cortisol pattern:

- Blunted morning peak (exhausted stress response)

- Flatter curve throughout day (less variation)

- Elevated evening cortisol (incomplete daily decline)

- Higher nighttime baseline

This pattern is called “HPA axis dysregulation” or colloquially “adrenal fatigue” (though adrenal glands aren’t actually fatigued — it’s a regulatory issue).

Research on chronic stress and cortisol rhythms found that individuals experiencing prolonged stress show flattened diurnal cortisol curves with elevated evening levels persisting for months, correlating with insomnia, fatigue, and metabolic dysfunction.

My cortisol testing: During my worst sleep period, I did salivary cortisol testing (4-point curve across the day). My morning cortisol was low-normal (should be high). My evening cortisol at 10 PM was elevated (should be low). My curve was essentially flat — minimal variation between 8 AM and 10 PM.

This explained everything. My body wasn’t producing the cortisol surge needed for morning alertness, nor the evening decline needed for sleep. I was stuck in a dysregulated middle ground.

Fixing this required addressing chronic stress sources (job change, therapy, boundaries around work) plus targeted interventions (morning light exposure to boost morning cortisol, evening stress reduction to lower evening cortisol).

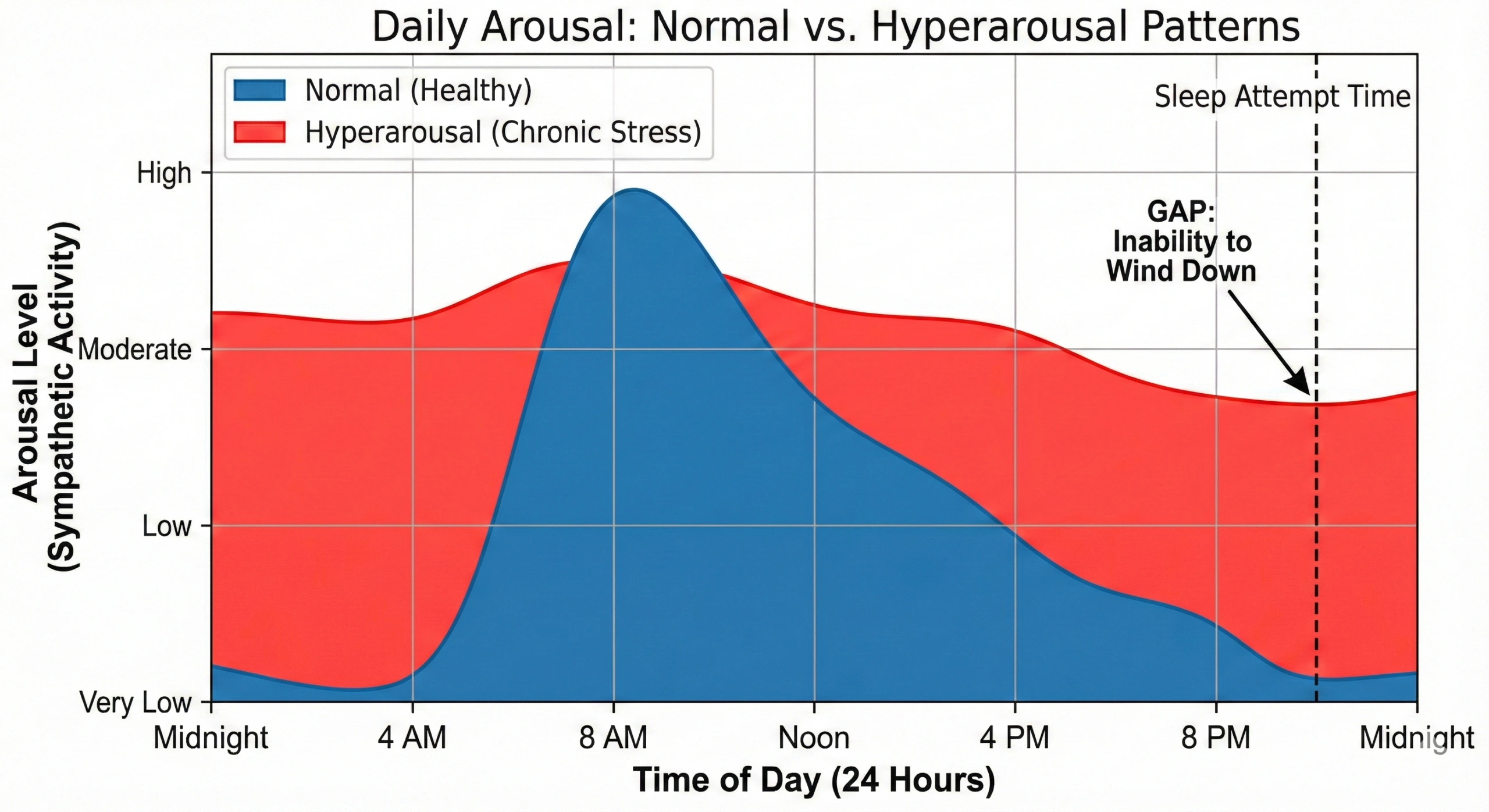

Understanding Chronic Hyperarousal State

If you chronically struggle with sleep onset, you’re likely experiencing hyperarousal — a state where your nervous system maintains elevated activation even during rest periods.

What Is Hyperarousal?

Hyperarousal is a physiological and cognitive state characterized by elevated sympathetic nervous system activity, increased sensory sensitivity, racing thoughts, and difficulty disengaging from external and internal stimuli.

Physiological markers of hyperarousal:

- Elevated resting heart rate (>70-75 bpm)

- High heart rate variability (HRV) indicating sympathetic dominance

- Increased muscle tension (particularly jaw, neck, shoulders)

- Elevated core body temperature

- Faster metabolic rate

- Heightened startle response

Cognitive markers of hyperarousal:

- Racing thoughts, difficulty “turning off” thinking

- Rumination (repetitive negative thoughts)

- Difficulty with attentional disengagement (can’t stop focusing on problems)

- Hypervigilance to potential threats or problems

- Mental restlessness even when body is tired

Behavioral markers:

- Difficulty sitting still or relaxing

- Constant activity or multitasking

- Checking behaviors (phone, email, news)

- Difficulty with unstructured downtime

Research on hyperarousal and insomnia demonstrates that chronic insomnia is fundamentally a disorder of hyperarousal, with elevated arousal present across the 24-hour day, not just at night.

My hyperarousal symptoms:

- Resting heart rate 75-82 bpm (now 58-65 bpm after addressing hyperarousal)

- Constant muscle tension in shoulders and jaw

- Inability to watch TV without also checking phone

- Restless leg movements even when sitting

- Startling easily at unexpected sounds

- Mind racing with task lists and problems even during “relaxation” activities

I didn’t realize I was in a chronic hyperarousal state because it was my baseline normal. I thought everyone’s brain worked this way. It wasn’t until I experienced true relaxed parasympathetic state (after months of intervention) that I understood how abnormal my previous baseline was.

The 24-Hour Hyperarousal Pattern

Hyperarousal isn’t just a nighttime problem. People with sleep onset insomnia often show elevated arousal throughout the entire 24-hour period.

Daytime hyperarousal manifestations:

- Higher average heart rate and blood pressure

- Elevated cortisol and other stress hormones

- Increased metabolic rate (burning more energy at rest)

- Cognitive rumination and difficulty with present-moment focus

- Physical tension and restlessness

Studies using polysomnography and metabolic measurements found that individuals with chronic insomnia have higher 24-hour energy expenditure and elevated core body temperature compared to good sleepers, indicating a global hypermetabolic state.

Why 24-hour hyperarousal matters:

You can’t simply “turn off” hyperarousal at bedtime if you’ve been in that state all day. The nervous system doesn’t have an off switch. It requires gradual downregulation through consistent interventions across the entire day, not just at bedtime.

This is why typical “sleep hygiene” advice (warm bath, chamomile tea, meditation before bed) often fails. These interventions are too little, too late. You’re trying to shift your nervous system from high sympathetic tone to parasympathetic in 30-60 minutes, when it’s been stuck in sympathetic all day.

What worked for me: Addressing hyperarousal required all-day interventions, not just bedtime routines:

- Morning: Regulating cortisol awakening response through light exposure

- Throughout day: Scheduled “vagal breaks” (10-minute breathing exercises every 2-3 hours)

- Afternoon: Moderate exercise to process stress hormones

- Evening: Structured wind-down starting 3 hours before bed, not 30 minutes

Cognitive Hyperarousal — The Racing Mind

Physical hyperarousal (elevated heart rate, muscle tension) is one component. Cognitive hyperarousal — the inability to quiet your thinking — is equally problematic.

Manifestations of cognitive hyperarousal:

- Rumination: Repetitively thinking about past events, mistakes, or problems without resolution

- Worry: Future-oriented repetitive thoughts about potential problems or threats

- Planning: Mental task-listing, problem-solving, organizing when you should be disengaging

- Hypervigilance: Heightened awareness of environment, scanning for threats or problems

- Attentional bias: Difficulty shifting attention away from stressors toward neutral or positive stimuli

Research on cognitive arousal and insomnia shows that pre-sleep cognitive activity (racing thoughts, worry, rumination) is one of the strongest predictors of sleep onset latency, often more predictive than physical arousal measures.

Why cognitive hyperarousal is so persistent:

Your brain evolved to prioritize threats and unsolved problems. From a survival perspective, ignoring a potential threat to sleep was far more dangerous than missing one night of sleep. This bias toward arousal and vigilance is hardwired.

In modern life, our “threats” are rarely life-threatening (deadlines, social conflicts, financial stress), but our brain treats them with the same urgency. You can’t fall asleep because your brain is saying “we have unresolved problems that require attention.”

My cognitive hyperarousal pattern:

Getting into bed would trigger an avalanche of thoughts:

- Task lists for tomorrow

- Replaying conversations from the day

- Worrying about upcoming deadlines

- Planning solutions to work problems

- Remembering things I forgot to do

- Anticipating potential future problems

I’d try to suppress these thoughts, which paradoxically made them stronger (thought suppression rebound effect). I’d get frustrated with myself for “not being able to stop thinking,” which created additional stress, further activating arousal.

What finally helped: Externalization strategies (writing down thoughts before bed so brain could “let go”) and acceptance-based approaches (allowing thoughts to be present without engaging with them).

My 3-Year Battle With Chronic Sleep Onset Insomnia

For three years, I averaged 60-90 minutes to fall asleep every night. I tried everything — supplements, meditation apps, sleep restriction, stimulus control, medication. Nothing consistently worked until I understood and addressed the root cause: chronic hyperarousal.

How It Started (The Acute Stressor)

My sleep onset problems began during a particularly stressful work period. I was managing a major project with a tight deadline, working 60+ hour weeks, fielding client calls at 9-10 PM, and carrying constant background anxiety about whether everything would come together.

Week 1-2: Lying awake 30-45 minutes nightly, mind racing about work. I’d eventually fall asleep exhausted.

Week 3-4: Sleep onset latency increased to 60 minutes. I started getting anxious about sleep itself (“I need to sleep, I have to present tomorrow”). The anxiety made it worse.

Week 5-8: The project ended successfully, but my sleep didn’t improve. This is when I should have recovered, but the insomnia persisted. I’d developed conditioned arousal — my bedroom and bedtime itself triggered anxiety and arousal.

Months 3-6: Sleep onset latency stabilized at 75-90 minutes. I became obsessed with sleep, reading everything I could find, trying every recommendation. The obsession itself became another source of stress.

This is the typical pattern of acute insomnia transitioning to chronic insomnia. An initial stressor creates sleep disruption, but even after the stressor resolves, the insomnia continues due to conditioned arousal and maladaptive compensatory behaviors.

The Desperation Phase (Trying Everything)

Supplements I tried:

- Melatonin (3mg, 5mg, 10mg) — minimal effect, next-day grogginess

- Magnesium glycinate — felt slightly more relaxed, no change in sleep onset

- L-theanine — no noticeable effect

- Valerian root — no effect

- CBD oil — expensive placebo

- GABA — didn’t cross blood-brain barrier effectively

Behavioral interventions:

- Sleep restriction therapy — made me more sleep-deprived without fixing onset

- Stimulus control — helped somewhat, but didn’t address root hyperarousal

- Progressive muscle relaxation — provided temporary relief but didn’t resolve core issue

- Guided meditation apps (Calm, Headspace) — helped on occasional nights, inconsistent

- Weighted blanket — cozy but didn’t improve sleep onset

Medications (prescribed by doctor):

- Ambien (zolpidem) — knocked me out but sleep quality was poor, felt hungover

- Trazodone — helped with sleep onset, but next-day fatigue was debilitating

- Hydroxyzine (antihistamine) — worked initially, then tolerance developed within 2 weeks

What all these approaches missed: They were treating symptoms (inability to sleep) rather than the underlying cause (chronic sympathetic activation and hyperarousal).

Pills could force sleep (sometimes), but they didn’t address why my nervous system was stuck in arousal. Behavioral techniques could occasionally override arousal, but they didn’t reduce baseline arousal levels.

I was fighting my biology with willpower and interventions, rather than addressing the regulatory dysfunction.

The Turning Point (Understanding Autonomic Dysregulation)

After 18 months of failed interventions, I came across research on heart rate variability (HRV) and autonomic function. I learned that chronic insomnia is fundamentally an arousal disorder, not a sleep disorder.

I bought a chest strap HRV monitor and started tracking. The data was revealing:

My autonomic metrics:

- Resting heart rate: 78-82 bpm (should be 60-70 bpm for my age/fitness)

- HRV (RMSSD): 25-32 ms (low, indicating sympathetic dominance)

- Stress score: Consistently “high” throughout the day

- Recovery score: Rarely exceeded “moderate”

For comparison, good sleepers typically have:

- Resting heart rate: 55-65 bpm

- HRV: 50-80 ms

- Clear circadian variation in HRV (higher at night)

My numbers showed chronic sympathetic dominance with minimal circadian variation. I was stuck in “fight or flight” from morning through attempted sleep.

This wasn’t a psychological problem I could think my way out of. It was a physiological dysregulation that required systematic downregulation of my overactive stress response system.

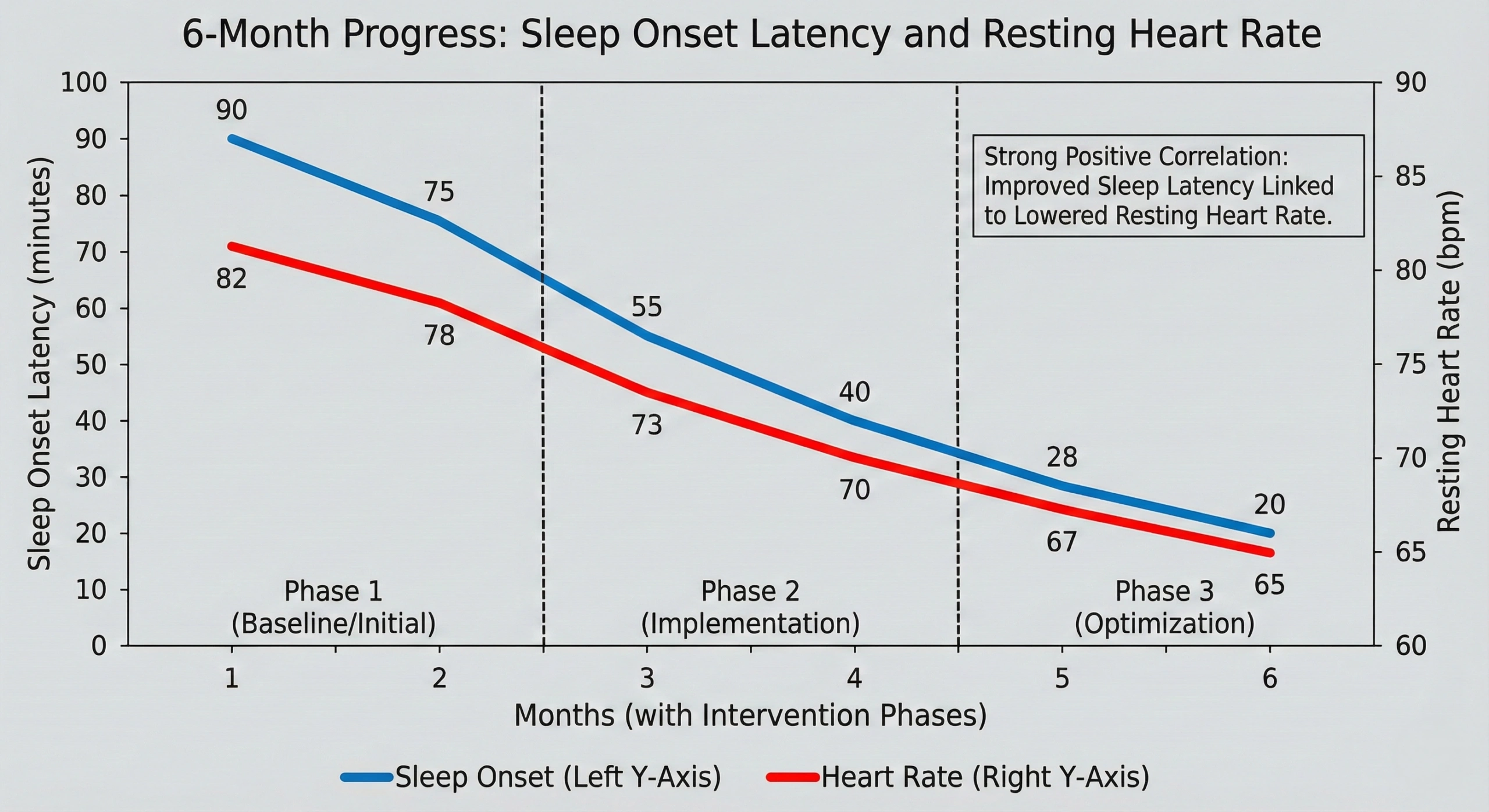

The Systematic Fix (What Actually Worked)

Once I understood the problem was autonomic dysregulation, I focused on interventions proven to shift autonomic balance toward parasympathetic dominance.

Phase 1: Reduce daytime arousal triggers (Month 1-2)

Morning:

- Caffeine limited to before 10 AM (was consuming until 3 PM)

- Morning sunlight exposure (30 minutes to regulate circadian cortisol)

- No checking work email until after breakfast

Throughout day:

- Scheduled “parasympathetic breaks” every 2 hours: 5-10 minutes of box breathing

- Lunch away from desk, outside when possible

- Reduced news/social media consumption (major anxiety trigger)

Evening:

- Hard cutoff on work at 6 PM (no email, no calls)

- Eliminated evening news (replaced with music or podcasts)

- Dimmed all lights after 7 PM

Results after 2 months:

- Resting heart rate dropped to 72-75 bpm

- Sleep onset improved from 90 minutes to 60 minutes

- Less daytime anxiety

Phase 2: Evening downregulation protocol (Month 3-4)

7:00-8:00 PM:

- Moderate walk outdoors (30 minutes)

- Warm shower (facilitates temperature drop)

- Gentle stretching while listening to calming music

8:00-9:00 PM:

- Dim lighting only (candles or low-wattage lamps)

- Reading fiction (escapist, not stimulating)

- No screens (occasionally used iPad with blue-blocker + night shift on lowest brightness)

9:00-10:00 PM:

- Journaling (externalize thoughts, worries, to-do lists)

- 10 minutes of yoga nidra or guided body scan

- Bedroom temperature set to 64°F

- White noise machine on

10:00 PM:

- Lights out

- If not asleep in 20 minutes, get up and read in dim light until drowsy (stimulus control)

Results after 2 months:

- Resting heart rate: 66-70 bpm

- HRV improved to 38-45 ms

- Sleep onset: 30-45 minutes (major improvement)

- Less anxiety about sleep itself

Phase 3: Addressing residual cognitive arousal (Month 5-6)

Despite physiological improvements, I still had racing thoughts. Added:

- Cognitive therapy techniques (challenging anxiety-producing thoughts)

- Mindfulness practice (allowing thoughts without engaging)

- “Thought dumping” journaling at 8:30 PM (write every worry, plan, thought to externalize)

Final results (Month 6):

- Resting heart rate: 62-68 bpm

- HRV: 48-58 ms

- Sleep onset: 15-25 minutes (normal range)

- Sleep quality dramatically improved

- No longer anxious about sleep

What I Learned (Key Insights)

1. Sleep onset insomnia is an arousal problem, not a sleep problem

You don’t have “broken sleep.” You have an overactive stress response system. Fix the arousal, and sleep follows naturally.

2. Bedtime interventions alone are insufficient

You can’t downregulate sympathetic activation in 30 minutes before bed if you’ve been sympathetically activated for 16 hours. You need all-day arousal management.

3. Medication masks the problem but doesn’t fix it

Sleep meds can force sleep, but they don’t address why your nervous system is stuck in arousal. When you stop the meds, the problem returns.

4. The fix is boring but effective

There’s no quick solution. Systematic lifestyle changes that reduce arousal across 24 hours are what work. It takes months, not days.

5. Tracking helps

HRV and resting heart rate provided objective feedback that my interventions were working, even before subjective sleep improved. This kept me motivated during the slow progress weeks.

6. The problem can fully resolve

After years of insomnia, I doubted I’d ever sleep normally again. But once I addressed the root autonomic dysregulation, my sleep became consistently good. It’s not just “managed” — it’s resolved.

How Modern Environments Create Chronic Arousal

Even without major life stressors, modern life systematically creates conditions for chronic sympathetic activation through constant overstimulation.

The Digital Overstimulation Problem

Constant connectivity:

- Average person checks phone 80-150 times per day

- Push notifications create frequent micro-stressors

- Email/messages create expectation of immediate response

- Social media provides endless novel stimuli

Each notification, each email check, each context switch creates a small cortisol response. Individually trivial, but cumulatively they maintain elevated baseline arousal throughout the day.

Research on smartphone use and stress found that high-frequency phone users show elevated cortisol, reduced HRV, and poorer sleep quality compared to moderate users, with the relationship partially mediated by sustained attention fragmentation.

Blue light at the wrong time:

Screens emit blue light (450-480nm) that’s detected by melanopsin-containing photoreceptors in your eyes. This blue light:

- Suppresses melatonin production (even at relatively low intensities)

- Activates alertness centers in the brain

- Delays circadian phase

- Increases sympathetic tone

Studies show that 2-3 hours of evening screen exposure reduces melatonin by 50% and delays sleep onset by 30-90 minutes.

Information overload:

The sheer volume of information modern people process daily is unprecedented:

- News (often negative, triggering stress response)

- Work communications (emails, Slack, meetings)

- Social media (comparison, FOMO, outrage)

- Entertainment (streaming, podcasts, articles)

Your brain evolved to process maybe 100-200 discrete pieces of information per day in a tribal setting. Modern life throws thousands of inputs at you daily. This creates cognitive overload that keeps your brain in an activated, processing state rather than allowing genuine rest.

My phone addiction: At my worst, I was checking my phone every 5-10 minutes. Email, text, Twitter, news. Each check triggered a small arousal response — anticipation, sometimes disappointment, sometimes stress from what I saw.

I tracked this for a week: 120+ phone unlocks per day. That’s 120+ micro-activations of my sympathetic nervous system. No wonder I couldn’t downregulate by bedtime.

I implemented a “phone sunset” rule: phone goes into airplane mode at 7 PM. No exceptions. The first week was uncomfortable (FOMO, boredom). By week two, I noticed evenings felt calmer. My HRV improved, and sleep onset shortened.

Environmental Noise and Sensory Stimulation

Urban noise pollution:

- Traffic (unpredictable, arousing)

- Sirens and horns (acute stressors)

- Neighbors (footsteps, voices, music)

- HVAC systems (constant background hum)

Even when you habituate consciously to noise, your nervous system continues responding. Research shows that chronic noise exposure elevates cortisol and sympathetic activity even when people report being “used to it”.

Light pollution:

Most modern environments never truly get dark:

- Streetlights (maintaining arousal signals at night)

- Indoor lighting (too bright in evening, too dim in morning)

- Device lights (LEDs on electronics)

- Light from other rooms/neighbors

This constant low-level light exposure suppresses melatonin and prevents the circadian signal for “night” from being clear.

Sensory overload in general:

Modern environments bombard you with stimuli:

- Visual: ads, screens, signs, notifications

- Auditory: music, conversations, machinery, traffic

- Olfactory: perfumes, pollution, food smells

- Tactile: clothing, temperature fluctuations, furniture

This constant sensory input keeps your brain in processing mode. There’s no genuine “quiet” for most people — no sensory deprivation that allows the nervous system to fully downregulate.

My apartment’s arousal triggers: I lived in a city apartment with:

- Streetlights shining directly into bedroom (constant 10-15 lux at night)

- Traffic noise until 1-2 AM (intermittent sirens waking me)

- Neighbor footsteps overhead (unpredictable, arousing)

- Refrigerator hum in adjacent room

I thought I’d adapted to these, but when I finally addressed them (blackout curtains, white noise machine, refrigerator on timer), my sleep improved dramatically. My nervous system had been maintaining low-level arousal to monitor these stimuli, even when I wasn’t consciously aware of them.

The “Always On” Work Culture

Modern work culture creates expectation of constant availability:

- Email checking outside work hours

- Evening/weekend calls and messages

- Remote work blurring home/work boundaries

- “Grind culture” valorizing overwork

This prevents genuine psychological detachment from work stress. Research on work-related rumination shows that inability to psychologically detach from work during off-hours correlates strongly with sleep onset insomnia, elevated cortisol, and burnout.

The anticipatory arousal problem:

When you’re “on call” mentally (even without explicit work requirements), your brain maintains vigilance. You’re subconsciously monitoring for potential work issues, which prevents full relaxation.

I experienced this severely. Even when I wasn’t actively working in the evening, I was mentally “available” — part of my attention was monitoring for email notifications, anticipating tomorrow’s demands, rehearsing responses to potential issues.

Setting a hard boundary (no work communication after 6 PM, none on weekends) initially created anxiety (“What if something urgent happens?”). But after 2 weeks, I realized: nothing urgent enough to require immediate evening response ever actually happened. And my sleep dramatically improved.

How to Reduce Arousal and Fall Asleep Faster

Understanding the problem is essential, but here’s what actually works to downregulate hyperarousal and improve sleep onset.

Daytime Arousal Management (The Foundation)

You cannot fix evening hyperarousal without addressing daytime arousal. These interventions shift your baseline sympathetic tone downward.

Morning cortisol optimization:

- Bright light exposure within 2 hours of waking (sets healthy cortisol rhythm)

- Light breakfast within 30 minutes of waking (stabilizes blood sugar)

- Avoid checking stressful content (email, news) before 9 AM

Studies show that morning bright light exposure improves cortisol rhythm, reducing evening levels and improving sleep onset.

Caffeine timing:

- Last caffeine by 10 AM-12 PM (5-6 hour half-life means it’s still active at bedtime if consumed later)

- Total caffeine <200mg if you’re sensitive

- Switch to decaf or herbal tea after noon

Scheduled downregulation breaks:

- Every 2-3 hours: 5-10 minute breathing exercise

- Box breathing (4 seconds in, 4 hold, 4 out, 4 hold) or extended exhale breathing (4 in, 8 out)

- These activate parasympathetic nervous system and lower cortisol

Research on brief breathing interventions demonstrates that even 5 minutes of slow, paced breathing significantly reduces sympathetic activity and cortisol.

Afternoon exercise:

- 30-60 minutes of moderate aerobic activity

- Timing: 3-6 hours before bedtime (allows cortisol to decline before sleep)

- Helps process stress hormones and build sleep pressure

- Avoid intense exercise within 3 hours of bedtime (can delay sleep onset)

Evening Wind-Down Protocol (3-Hour Process)

Effective wind-down requires TIME. You can’t shift from high arousal to sleep-ready in 30 minutes.

3 hours before bed: Begin transition

- Stop work completely (no email, no work-related activities)

- Dim all lights by 50% (begin signaling “evening” to circadian system)

- Switch to relaxing activities (reading, light conversation, gentle movement)

- No intense or stimulating content (action movies, heated debates, stressful news)

2 hours before bed: Deepen relaxation

- Further dim lights (candles or low-wattage lamps only)

- Screen use only if necessary (use night shift mode + lowest brightness + blue-blocking glasses)

- Physical relaxation: stretching, gentle yoga, warm shower

- Externalize thoughts: journal worries, to-do lists, racing thoughts

1 hour before bed: Preparation for sleep

- Bedroom preparation (cool temperature 60-67°F, total darkness, white noise)

- Personal hygiene routine (signals bedtime is approaching)

- Final relaxation: meditation, body scan, progressive muscle relaxation

- Read fiction (not work-related or stimulating)

Bedtime:

- Lights out when genuinely drowsy (not by clock)

- If not asleep in 20 minutes: get up, read in dim light until drowsy, try again

This protocol allows gradual downregulation rather than attempting an impossible rapid shift.

Cognitive Techniques for Racing Thoughts

Physical arousal reduction helps, but many people also need cognitive strategies for mental hyperarousal.

Thought externalization:

- Keep journal and pen by bed

- Write down any thought that’s keeping you awake

- This signals to your brain “we’ve captured this, we can let go now”

Cognitive defusion:

- Observe thoughts without engaging: “I’m having the thought that I can’t sleep” (rather than “I can’t sleep”)

- Label thoughts as “planning,” “worrying,” “remembering” (creates distance)

- Imagine thoughts as clouds passing by rather than requiring response

Acceptance-based approach:

- Don’t try to suppress thoughts (increases them via ironic process effect)

- Allow thoughts to be present without fighting them

- Redirect attention gently to body sensations, breath, or neutral focus

Research on cognitive therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) shows that cognitive restructuring and acceptance-based approaches significantly reduce sleep onset latency, particularly in people with high cognitive arousal.

What worked for me: I started “thought dumping” at 9 PM — writing every worry, task, plan, and random thought on paper. Just the act of externalizing reduced the urgency my brain felt to keep processing them. Combined with allowing remaining thoughts to be present without engaging, this reduced cognitive arousal substantially.

Bedroom Environment Optimization

Your sleep environment directly affects arousal level.

Temperature:

- 60-67°F (cool enough to facilitate core temperature drop)

- Use breathable bedding (cotton, linen)

- Warm socks if feet are cold (promotes vasodilation)

Darkness:

- Complete darkness (<1 lux)

- Blackout curtains, cover all LEDs

- Sleep mask if complete darkness impossible

Noise:

- White noise machine or fan (masks intermittent sounds)

- Earplugs if noise severe

- Address specific noise sources where possible

Bed association:

- Use bed only for sleep and sex (not work, TV, phone use)

- If can’t sleep after 20 minutes, leave bedroom (maintain bed-sleep association)

These environmental factors reduce sensory arousal and strengthen circadian signals for sleep.

Recognizing When Self-Help Isn’t Enough

Most sleep onset insomnia can improve with the interventions described, but some situations require professional treatment.

Signs You Need Professional Evaluation

Seek medical evaluation if:

- Sleep onset insomnia persists >3 months despite consistent interventions

- Daytime functioning severely impaired (can’t work, dangerous activities affected)

- Co-occurring mental health conditions (depression, anxiety disorders)

- Suicidal thoughts or severe mood changes

- Physical health concerns (chest pain, extreme fatigue, unexplained symptoms)

- Suspected sleep disorders (sleep apnea, restless leg syndrome, narcolepsy)

When to consider therapy (CBT-I):

- Strong conditioned arousal response to bedroom/bedtime

- Severe anticipatory anxiety about sleep

- Sleep onset insomnia plus generalized anxiety or depression

- Maladaptive sleep behaviors resistant to change

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) is the gold standard treatment for chronic insomnia, with effectiveness equal to or better than medication. Research shows that CBT-I produces lasting improvements in 70-80% of chronic insomnia patients.

When medication might be appropriate:

- Acute insomnia during crisis (short-term use)

- CBT-I and lifestyle changes haven’t worked after 3+ months

- Severe impairment requiring immediate intervention

- Always under medical supervision, not as first-line treatment

Life After Fixing Sleep Onset Insomnia (What Changed)

It’s been two years since I resolved my chronic sleep onset insomnia. My sleep isn’t perfect every night, but the transformation is profound.

My Current Sleep Pattern

Typical night now:

- 10:00-10:15 PM: Get in bed when genuinely drowsy

- 10:15-10:25 PM: Fall asleep (10-15 minutes average)

- Wake 1-2 times briefly for bathroom

- 6:00-6:30 AM: Wake naturally feeling refreshed

Compare to previous pattern:

- 11:00 PM: Force myself to bed despite not being tired

- 11:00 PM-12:30 AM: Lie awake with racing thoughts

- 12:30 AM: Finally fall asleep from exhaustion

- Wake 5-7 times, often for 15-30 minutes

- 7:00 AM: Alarm jolts me awake, feel terrible

The difference is life-changing. I no longer dread bedtime. Sleep is no longer a source of anxiety and frustration.

What I Maintain (The Non-Negotiables)

Even after resolution, I maintain certain practices because stopping them leads to backsliding.

Daily non-negotiables:

- Morning light exposure (15-20 minutes outdoors by 8 AM)

- Caffeine cutoff (no caffeine after 11 AM)

- Evening phone sunset (airplane mode at 8 PM)

- Bedroom environment (65°F, total darkness, white noise)

5-6 days per week:

- Afternoon exercise (30-45 minutes, 4-6 PM)

- Evening wind-down (starting 7:30-8 PM)

- Thought dumping journal (9 PM)

What I’m flexible about:

- Bedtime can vary 30-60 minutes depending on actual drowsiness

- Weekend schedule slightly later (but within 1 hour of weekday)

- Occasional evening social events (but still maintain core practices)

If I start slipping on the non-negotiables (traveling, busy periods, laziness), I notice sleep onset increasing within 3-5 days. My nervous system is still predisposed to hyperarousal — I need ongoing regulation practices.

How My Life Changed (Beyond Sleep)

Fixing sleep onset had ripple effects far beyond just sleeping better.

Physical health:

- Resting heart rate: 82 bpm → 62 bpm

- HRV: 28 ms → 58 ms

- Blood pressure: 135/85 → 118/75

- Lost 12 lbs without diet changes (reduced stress-driven eating)

- Significantly fewer colds/infections

Mental/emotional:

- Baseline anxiety dramatically reduced

- Emotional reactivity way down (less irritable, more patient)

- Cognitive performance improved (memory, focus, decision-making)

- Depression that I thought was personality-based resolved

Relationships:

- Less withdrawn and irritable with partner

- More present in conversations (not mentally exhausted)

- More capacity for social connection

Work:

- Productivity increased despite working fewer hours

- Better focus and fewer mistakes

- Improved creativity and problem-solving

The common thread: chronic sleep deprivation from insomnia was affecting every domain of my life. I’d normalized the dysfunction, thinking “this is just how I am.” Turns out, it was fixable.

Occasional Bad Nights (How I Handle Them Now)

I still have occasional nights where sleep onset takes 30-45 minutes instead of 10-15. This happens maybe once per month, usually tied to identifiable stressors (work deadline, travel, conflict).

How I respond now vs. before:

Before (catastrophizing):

- Panic: “Oh no, it’s starting again, I’m going to have insomnia forever”

- Performance anxiety: “I HAVE to fall asleep”

- Frustration and anger at myself

- Abandoning all practices because “nothing works”

Now (acceptance and problem-solving):

- Recognition: “I’m more activated than usual tonight”

- Curiosity: “What’s different today?” (usually can identify: late caffeine, stressful evening, skipped exercise)

- Action: Get up after 20 minutes, read until drowsy, try again

- Perspective: “One bad night isn’t chronic insomnia returning”

- Resume practices next day

This mindset shift is crucial. Bad nights don’t spiral into chronic insomnia anymore because I don’t catastrophize them into a crisis.

Understanding and Fixing Sleep Onset Insomnia

If you lie in bed exhausted but unable to fall asleep, you’re experiencing physiological hyperarousal — your sympathetic nervous system is active when it should be shutting down.

The core problem isn’t psychological weakness or “bad sleep habits.” It’s nervous system dysregulation, often driven by chronic stress, cortisol dysregulation, and modern overstimulation.

The solution isn’t found in bedtime routines alone. You need 24-hour arousal management:

- Morning light exposure to regulate cortisol rhythm

- Daytime practices that lower baseline arousal

- Evening wind-down that requires 2-3 hours, not 30 minutes

- Environment that reduces sensory arousal

- Cognitive strategies for racing thoughts

The fix takes time. Expect 6-12 weeks of consistent practice to see substantial improvement. This isn’t a quick fix, but it’s a real fix.

It’s worth it. Chronic insomnia affects every aspect of life — physical health, mental health, relationships, work. Resolving it is transformative.

🛠️ Action Plan: How to Fix It

Understanding the problem is Step 1. Fixing it requires a protocol. Based on your symptoms, check these guides:

Frequently Asked Questions

Why am I so tired all day but wide awake at night?

This is the classic “Tired but Wired” state, scientifically known as an inverted cortisol curve. Normally, cortisol (energy) should be high in the morning and low at night. Chronic stress flips this rhythm, causing fatigue during the day and a “second wind” of alertness when you try to sleep.

Does Melatonin actually help me fall asleep?

It depends. Melatonin is a signal to start sleep, not a sedative. It works well for fixing jet lag or circadian timing issues (e.g., if you are a night owl). However, if your insomnia is caused by anxiety or high cortisol, melatonin alone is usually ineffective.

Can I just catch up on sleep on the weekend?

No. Research shows that while you can reduce some sleepiness, you cannot fully undo the metabolic damage or neurocognitive deficits caused by sleep debt during the week. Consistency (waking up at the same time) is far more effective than “binge sleeping.”

When should I stop looking at screens?

Ideally, 2 hours before bed. Blue light from phones suppresses melatonin production by up to 50%, tricking your brain into thinking it is still daytime. If you must use screens, use strong blue-blocking glasses or set your device to “red mode.”

How do I know if I have clinical insomnia?

Generally, if you take longer than 30 minutes to fall asleep or wake up for more than 30 minutes at night, at least 3 times a week for 3 months, it is classified as chronic insomnia. In this case, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) is the gold standard treatment.

SOURCES

Research citations embedded throughout as hyperlinks to PubMed:

- Acute insomnia to chronic: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16335332/

- Insomnia and sympathetic activity: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17053484/

- Chronic stress and evening cortisol: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22301346/

- Evening cortisol and sleep onset: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11166365/

- Cortisol-melatonin antagonism: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21552190/

- Chronic stress and cortisol patterns: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24882388/

- Hyperarousal as core feature: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16335332/ (repeated)

- 24-hour hypermetabolic state: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11740196/

- Cognitive arousal and sleep onset: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12530990/

- Smartphone use and stress: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30444495/

- Screen time and melatonin: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21552190/ (repeated)

- Chronic noise and cortisol: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24051421/

- Work rumination and insomnia: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22339270/

- Morning light and cortisol: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30311830/

- Breathing and sympathetic activity: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28974359/

- CBT-I cognitive techniques: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25535399/

- CBT-I effectiveness: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26651948/