Sleep is not a single uniform state but a complex, cyclical process involving distinct stages, each serving different biological functions. Your brain progresses through approximately 4-6 sleep cycles per night, with each cycle lasting 90-120 minutes and containing alternating periods of non-REM (NREM) sleep and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep.

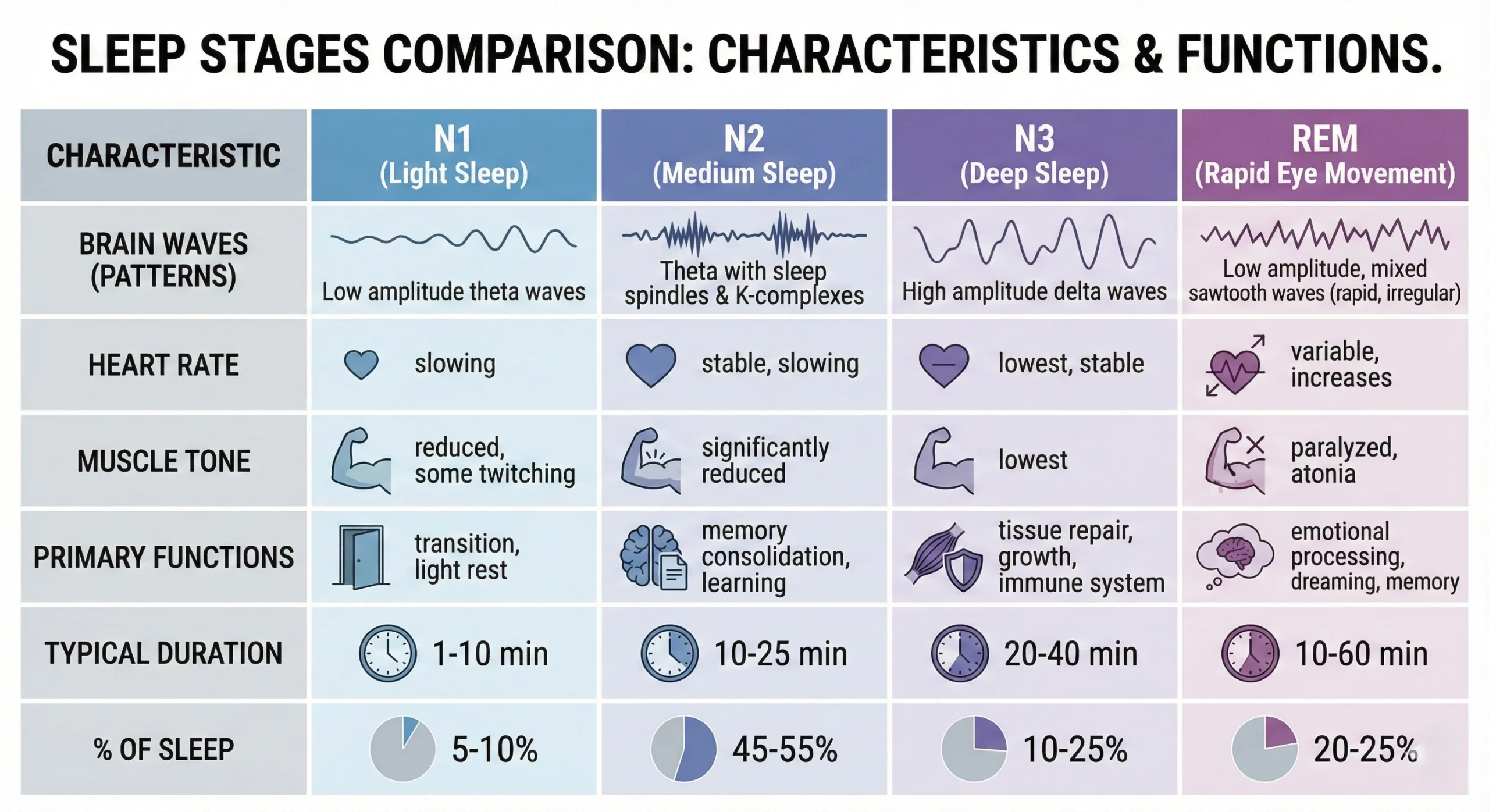

NREM sleep includes three stages: N1 (light transition), N2 (consolidated light sleep), and N3 (deep slow-wave sleep that restores physical energy). REM sleep, characterized by rapid eye movements and vivid dreaming, consolidates memories and processes emotions. Sleep architecture refers to the pattern and distribution of these stages throughout the night, with deep sleep dominating early cycles and REM sleep increasing in later cycles.

Understanding how sleep works mechanistically is essential for optimizing sleep quality rather than just duration.

Want Better Sleep Stats?

Theory is good, but tools get results. See the exact stack (mask, tape, supplements) I use to get 2+ hours of Deep Sleep every night.

Open Sleep HubWhat Happens When You Sleep (The 90-Minute Cycle)

Most people think of sleep as an on/off switch — you’re either awake or asleep. But sleep is actually a dynamic, structured process where your brain cycles through distinct physiological states multiple times per night.

Each complete sleep cycle lasts approximately 90-120 minutes and contains both NREM (non-rapid eye movement) sleep and REM (rapid eye movement) sleep. These cycles repeat 4-6 times throughout a typical 7-9 hour sleep period, with the composition of each cycle changing as the night progresses.

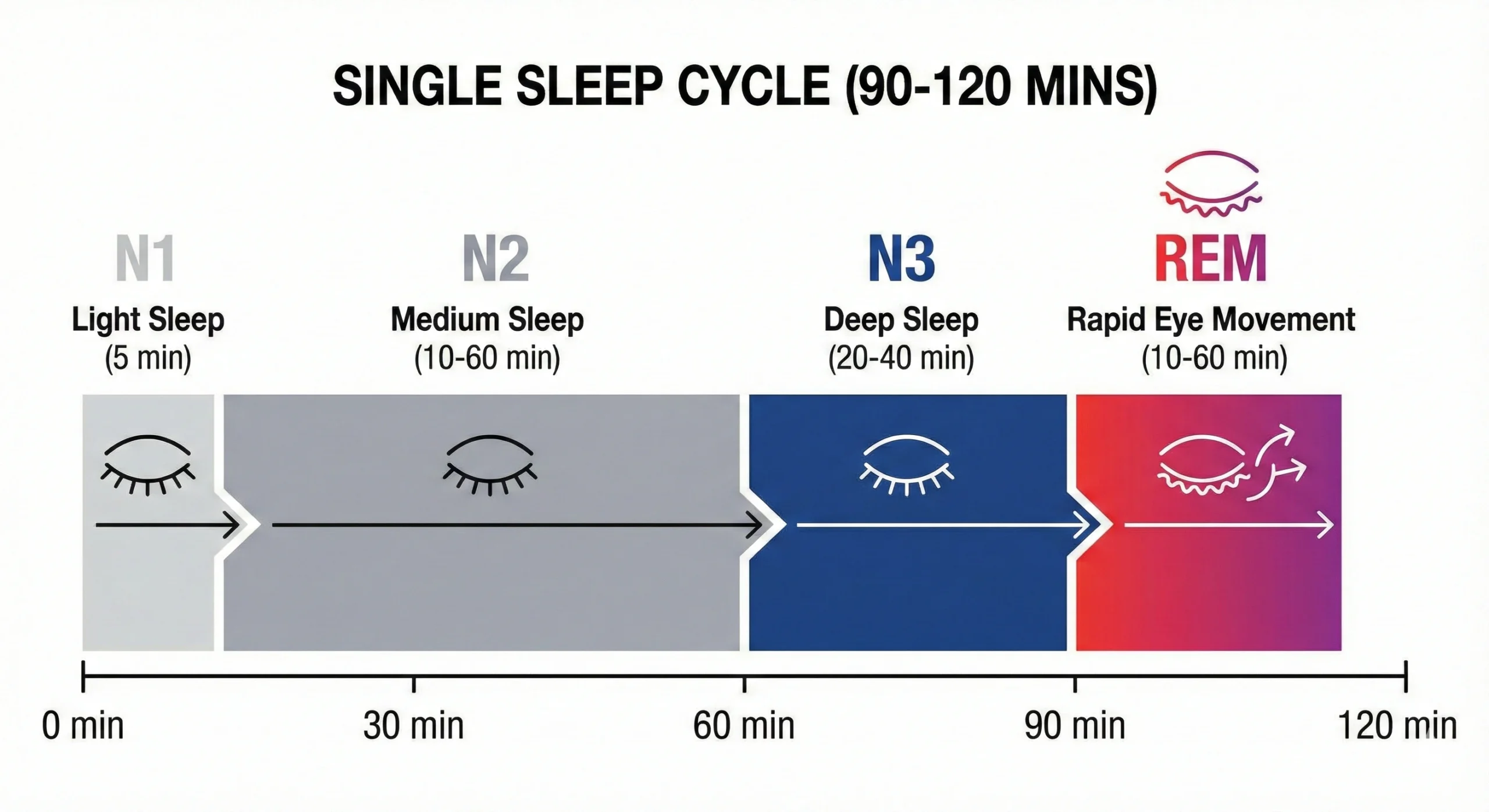

The Basic Structure of a Sleep Cycle

A standard sleep cycle progresses through stages in a predictable sequence, though the duration of each stage varies across the night.

Typical cycle progression:

- N1 (Stage 1 NREM): 1-5 minutes — transition from wake to sleep

- N2 (Stage 2 NREM): 10-60 minutes — light but consolidated sleep

- N3 (Stage 3 NREM): 20-40 minutes — deep slow-wave sleep (dominant in first half of night)

- REM sleep: 10-60 minutes — dreaming, memory consolidation (increases in later cycles)

After REM sleep, the cycle either repeats or (in the final cycle) transitions to waking.

Research on sleep architecture using polysomnography shows that healthy adults spend approximately 50-60% of sleep in N2, 15-25% in deep sleep (N3), 20-25% in REM, and less than 5% in N1.

What this means practically: If you sleep 8 hours (480 minutes), you’re getting roughly:

- 240-290 minutes of N2 light sleep

- 70-120 minutes of N3 deep sleep

- 95-120 minutes of REM sleep

- Less than 25 minutes in N1 transition sleep

The exact distribution varies by age, health, sleep debt, and individual factors, but these proportions represent normal healthy sleep architecture.

Why cycles matter: Waking up mid-cycle, particularly during deep sleep or REM, causes sleep inertia — that groggy, disoriented feeling that can last 15-30 minutes. Waking naturally at the end of a cycle (during light N2 or brief awakening between cycles) produces more refreshed waking.

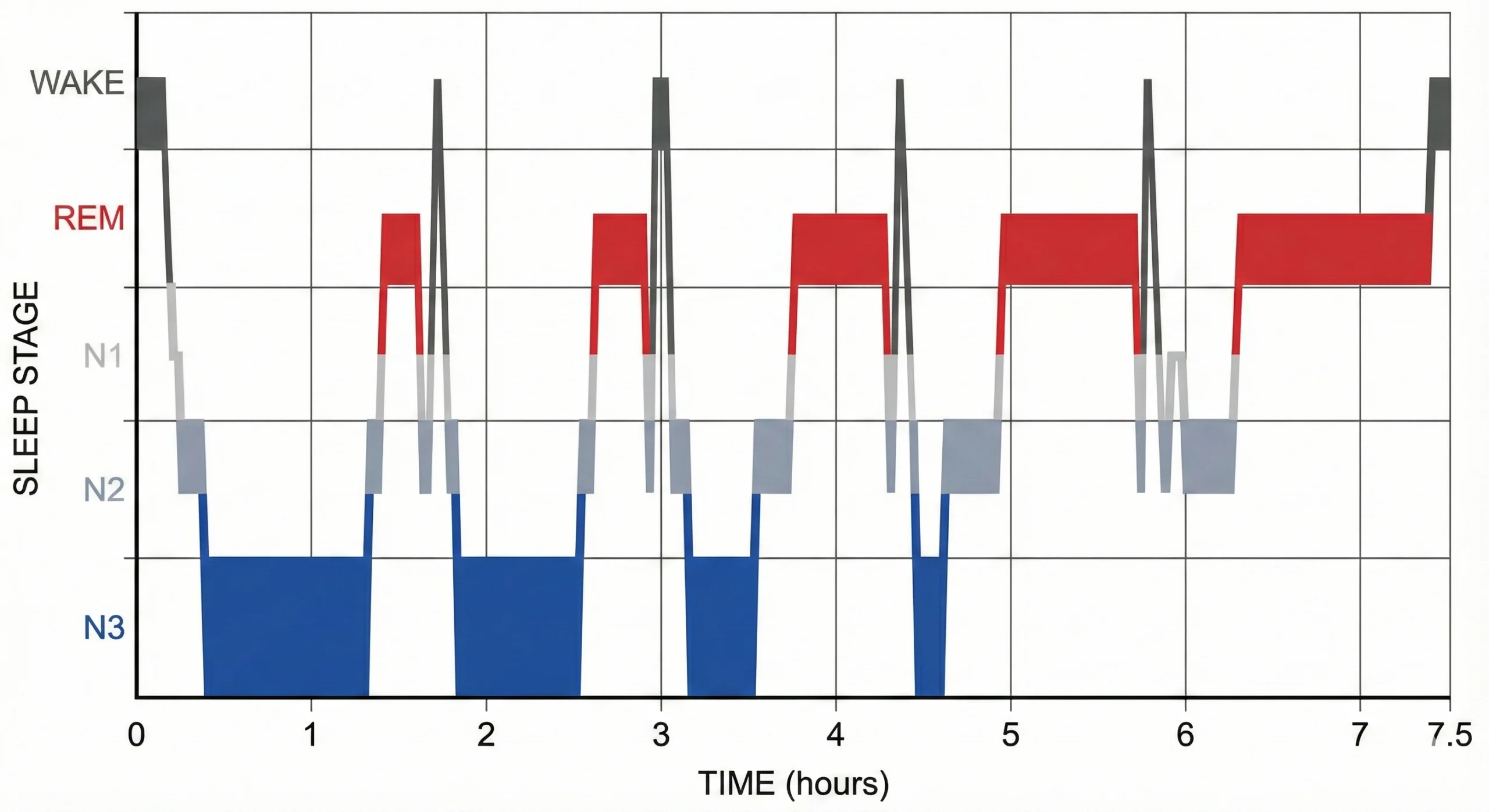

How Cycles Change Throughout the Night

Here’s where it gets interesting: not all sleep cycles are the same. The composition of cycles shifts dramatically from the first to the last cycle of the night.

Early night cycles (first 3 hours):

- Dominated by N3 deep sleep (30-40 minutes per cycle)

- Shorter REM periods (5-10 minutes)

- This is when most physical restoration occurs

Middle night cycles (hours 3-6):

- Moderate deep sleep (10-20 minutes per cycle)

- Increasing REM duration (15-30 minutes)

- Transition period

Late night cycles (final 1-3 hours):

- Minimal to zero deep sleep

- Long REM periods (30-60 minutes per cycle)

- This is when most dreaming and memory consolidation occurs

Studies on sleep cycle composition found that slow-wave sleep (N3) is primarily concentrated in the first third of the sleep period, while REM sleep predominates in the final third, with this distribution driven by circadian and homeostatic processes.

Why this matters for sleep duration: If you only sleep 5-6 hours, you’re primarily cutting off the late-night REM-rich cycles. You might get adequate deep sleep (which happens early) but insufficient REM sleep. This explains why chronic short sleep impairs memory and emotional regulation more than physical energy.

Conversely, if you go to bed very late but sleep for 8 hours, your circadian rhythm’s influence on sleep architecture can shift the distribution, potentially reducing overall deep sleep even with adequate duration.

My experience tracking cycles: When I started using a sleep tracker that showed cycle structure, I noticed that on nights when I only slept 6 hours (cut short by early alarm), I’d get roughly 80-90 minutes of deep sleep but only 60-70 minutes of REM. On 7.5-hour nights, deep sleep stayed similar (80-100 minutes) but REM increased to 100-120 minutes.

The extra 1.5 hours primarily added REM-rich cycles, which explained why I felt cognitively sharper and emotionally more stable on longer sleep nights even though physical energy wasn’t dramatically different.

The Ultradian Rhythm (90-120 Minute Periodicity)

The sleep cycle follows an ultradian rhythm — a biological rhythm shorter than 24 hours (circadian) but longer than an hour. This 90-120 minute periodicity is controlled by brainstem mechanisms and appears to continue subtly even during wakefulness.

Research suggests this is why focused work productivity tends to decline after 90-120 minutes of continuous effort, following a similar ultradian pattern. Your brain naturally operates in ~90-minute cycles of high and low activation states throughout the day and night.

Practical application: Timing sleep duration to complete full cycles (6 hours = 4 cycles, 7.5 hours = 5 cycles, 9 hours = 6 cycles) can reduce sleep inertia upon waking. Waking at 7.5 hours often feels more refreshing than waking at 8 hours if the latter interrupts mid-cycle.

This is why some people feel better on 7.5 hours than 8 hours — they’re completing 5 full cycles versus waking up 30 minutes into the 6th cycle.

What Happens During Deep Sleep (N3/Slow-Wave Sleep)

Deep sleep, technically called slow-wave sleep (SWS) or N3 sleep, is the most restorative sleep stage for physical recovery. This is when your body does its heavy maintenance work.

The Physiology of Deep Sleep

During deep sleep, your brain exhibits distinctive electrical patterns called slow waves or delta waves (0.5-4 Hz frequency). These are the slowest, largest amplitude brain waves you produce, indicating synchronized neuronal activity.

What’s happening physiologically:

- Brain activity: Cortex exhibits synchronized slow oscillations; this is the “offline” state where the brain consolidates synaptic connections

- Heart rate: Drops to its lowest point of the day (typically 40-60 bpm in healthy adults)

- Blood pressure: Decreases by 10-20% compared to waking levels

- Breathing: Slow, regular, and deep

- Body temperature: Continues declining to its nadir

- Muscle tone: Present but reduced (you can still move if needed, unlike REM atonia)

Hormonal changes during deep sleep:

- Growth hormone (GH): Peak secretion occurs during deep sleep, particularly in the first sleep cycle. Research shows that up to 70% of daily growth hormone secretion occurs during deep sleep, facilitating tissue repair and muscle growth.

- Cortisol: Reaches its lowest levels (preparation for the morning rise)

- Prolactin: Increases, supporting immune function

- Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH): Decreases to allow metabolic rest

Studies using functional brain imaging demonstrate that cerebral blood flow decreases by 25-30% during deep sleep compared to waking, indicating reduced metabolic demand and allowing the brain to focus energy on restorative processes rather than active information processing.

What Deep Sleep Does for Your Body

Deep sleep serves multiple critical functions, primarily focused on physical restoration and cellular maintenance.

Physical restoration:

- Muscle tissue repair and growth (facilitated by growth hormone)

- Bone strengthening and mineral deposition

- Immune system enhancement (production of cytokines and T-cells)

- Cellular debris clearance (increased glymphatic system activity)

Brain maintenance: The glymphatic system — a waste clearance system unique to the brain — is primarily active during deep sleep. Research shows that cerebrospinal fluid flow increases dramatically during slow-wave sleep, clearing metabolic waste products including beta-amyloid (implicated in Alzheimer’s disease).

During deep sleep, the space between brain cells increases by 60%, allowing cerebrospinal fluid to flush through and remove accumulated toxins from daytime metabolic activity. This is analogous to taking out the trash — your brain literally cleans itself during deep sleep.

Energy restoration: Deep sleep replenishes glycogen stores in the brain and body. Glycogen is the stored form of glucose, and its depletion during wakefulness contributes to fatigue. Deep sleep allows glycogen resynthesis without the competing energy demands of waking activity.

Memory consolidation (procedural): While REM sleep handles declarative memories (facts, events), deep sleep consolidates procedural memories — motor skills, habits, learned sequences. Studies on motor learning show that skill improvement from practice is enhanced by subsequent deep sleep, with the amount of improvement correlating with the quantity of slow-wave sleep.

How Much Deep Sleep Do You Need?

The amount of deep sleep varies by age, with younger people requiring and getting substantially more than older adults.

Age-related deep sleep requirements:

- Children (5-12 years): 20-25% of total sleep (2-3 hours per night)

- Teenagers (13-19 years): 18-23% of total sleep (1.5-2.5 hours)

- Adults (20-50 years): 15-20% of total sleep (1-1.5 hours)

- Older adults (50+): 10-15% of total sleep (0.5-1.5 hours)

Research on aging and sleep architecture demonstrates that slow-wave sleep declines by approximately 2% per decade after age 20, with the steepest decline occurring between ages 20-60. This is a normal aging process, not pathological, though excessive decline is associated with cognitive impairment.

For a typical adult sleeping 7.5 hours:

- Target: 80-120 minutes of deep sleep (18-25% of total)

- Below 60 minutes: Suboptimal, may indicate sleep disorders or poor sleep quality

- Above 120 minutes: Unusual in adults; seen in recovery sleep after severe deprivation

What reduces deep sleep:

- Alcohol consumption (suppresses slow-wave sleep while increasing light sleep)

- Bedroom temperature above 68°F (impairs temperature-dependent deep sleep entry)

- Sleep fragmentation from noise, light, or apnea (prevents progression into deep stages)

- Chronic stress (elevated cortisol prevents deep sleep entry)

- Caffeine late in the day (blocks adenosine receptors needed for deep sleep pressure)

My deep sleep journey: When I first started tracking, I was averaging 45-55 minutes of deep sleep per night (about 12-13% of my 7-hour sleep). This explained why I could sleep 7 hours and still feel exhausted — I was getting less than half the deep sleep I needed.

After optimizing my sleep environment (dropping bedroom temperature from 70°F to 65°F, total darkness, fixing circadian rhythm with morning light), my deep sleep increased to 75-95 minutes (18-22% of 7.5-hour sleep). The difference in how I felt was enormous — morning grogginess disappeared, physical recovery from exercise improved, and immune function noticeably strengthened (I stopped getting frequent colds).

What Happens During REM Sleep (Rapid Eye Movement Sleep)

REM sleep is the most fascinating and distinctive sleep stage, characterized by rapid eye movements, vivid dreams, and paradoxical brain activity that resembles waking states despite the body being paralyzed.

The Physiology of REM Sleep

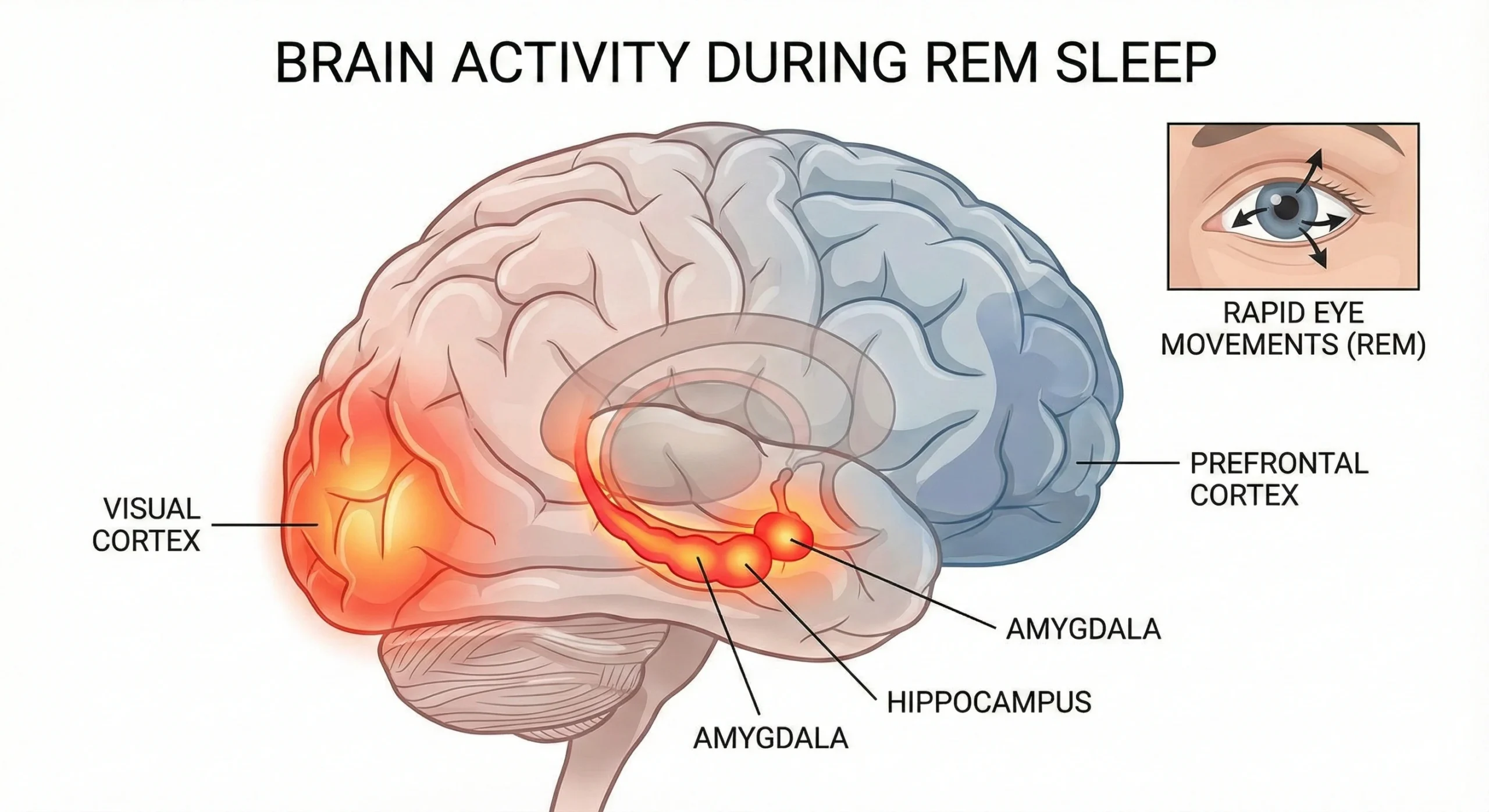

REM sleep is physiologically unique — your brain is highly active while your body is effectively paralyzed. This combination creates a safe environment for intense mental processing without physical movement.

Brain activity during REM:

- EEG patterns: Similar to waking beta and gamma waves (13-40 Hz), indicating high cortical activity

- Visual cortex: Intensely active (producing dream imagery)

- Limbic system: Highly activated (amygdala, hippocampus) — processing emotions and memories

- Prefrontal cortex: Deactivated — reduced logical reasoning, executive function, and reality testing (this is why dreams feel real but are often bizarre)

Studies using PET scans show that metabolic activity in visual association cortex and limbic structures increases by 20-40% during REM compared to waking, while prefrontal cortex activity drops by 10-30%.

Physical characteristics:

- Rapid eye movements: Eyes move rapidly under closed eyelids, tracking dream imagery

- Muscle atonia: Voluntary muscles (except diaphragm and eye muscles) are paralyzed by brainstem inhibition. This prevents you from physically acting out dreams.

- Heart rate variability: Increases significantly, with heart rate fluctuating between 50-90 bpm

- Breathing: Irregular, variable rate and depth

- Blood pressure: Variable, can spike during intense dream periods

- Body temperature regulation: Impaired — you don’t thermoregulate normally during REM (this is why bedroom temperature affects REM sleep)

- Penile/clitoral erection: Occurs automatically during REM regardless of dream content (used clinically to distinguish organic from psychological erectile dysfunction)

The muscle atonia during REM is critical. Research shows that dysfunction of this REM atonia mechanism causes REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD), where people physically act out dreams, sometimes violently, posing injury risk to themselves and bed partners.

What REM Sleep Does for Your Brain

REM sleep serves primarily cognitive and emotional functions rather than physical restoration.

Memory consolidation (declarative and emotional): REM sleep selectively strengthens memories that are emotionally salient or relevant to future goals while allowing irrelevant memories to decay. This is why you remember emotionally charged events more vividly — they’re preferentially consolidated during REM.

Research on memory and REM sleep demonstrates that REM deprivation selectively impairs learning of complex cognitive tasks and emotional memory formation while leaving simple procedural learning relatively intact (which relies more on deep sleep).

Emotional processing and regulation: During REM sleep, your brain replays emotional experiences in a neurochemically unique state — the amygdala (emotion center) is active, but norepinephrine (a stress neurotransmitter) is absent. This allows you to process emotional content without the associated stress response.

Studies by Matthew Walker’s lab found that REM sleep reduces the emotional tone of memories while preserving the factual content. This “overnight therapy” effect is why distressing events feel less emotionally intense after good sleep.

Without sufficient REM sleep, emotional memories retain their distress, and emotional reactivity increases. This explains why sleep-deprived people are more irritable, anxious, and emotionally volatile.

Creative problem-solving: REM sleep facilitates novel connections between disparate pieces of information. The deactivated prefrontal cortex allows unusual associations that would be suppressed during logical waking thought.

Research shows that REM sleep enhances creative problem solving and insight formation by 32% compared to equivalent time awake or NREM sleep. This is the neuroscience behind “sleep on it” — REM sleep literally rewires neural connections to find creative solutions.

Pattern recognition and abstraction: REM sleep extracts general rules and patterns from specific experiences. Studies on learning show that REM sleep improves ability to identify hidden patterns in data and transfer learned rules to new contexts.

How Much REM Sleep Do You Need?

Like deep sleep, REM sleep requirements vary by age, but the decline with aging is less pronounced than for deep sleep.

Age-related REM sleep distribution:

- Infants (0-1 year): 50% of sleep is REM (8-9 hours per day!) — critical for rapid brain development

- Children (2-10 years): 25-30% of sleep (2-3 hours per night)

- Teenagers/Young adults: 23-25% of sleep (2-2.5 hours)

- Adults (20-65 years): 20-25% of sleep (1.5-2 hours)

- Older adults (65+): 18-23% of sleep (1.2-1.8 hours)

For a typical adult sleeping 7.5 hours:

- Target: 90-120 minutes of REM sleep (20-25% of total)

- Below 70 minutes: Suboptimal, particularly for cognitive and emotional health

- Above 150 minutes: Unusual, may indicate REM rebound after deprivation

What reduces REM sleep:

- Alcohol (severely suppresses REM, particularly in first half of night)

- Many medications (SSRIs, beta blockers, some sleep aids)

- Sleep deprivation (though this creates REM rebound when sleep returns)

- Late-night eating (digestive activity interferes with REM)

- Bedroom temperature too high or too low (impaired thermoregulation affects REM)

- REM sleep preferentially occurs in the last third of sleep, so any reduction in total sleep duration disproportionately cuts REM

My REM sleep discovery: I initially focused only on deep sleep when optimizing, thinking physical restoration was most important. My deep sleep improved from 50 to 90 minutes, but my REM stayed stuck around 60-70 minutes (about 15-16% of sleep) even after environment fixes.

I realized the issue was total sleep duration. I was sleeping 6.5-7 hours, which gave adequate time for deep sleep (concentrated in first half) but insufficient time for REM-rich late cycles. When I extended to 7.5-8 hours, my REM jumped to 100-120 minutes (20-22%).

The cognitive difference was dramatic. My memory improved, I was less emotionally reactive to stressors, and my creative problem-solving noticeably sharpened. I hadn’t realized how REM-deprived I’d been.

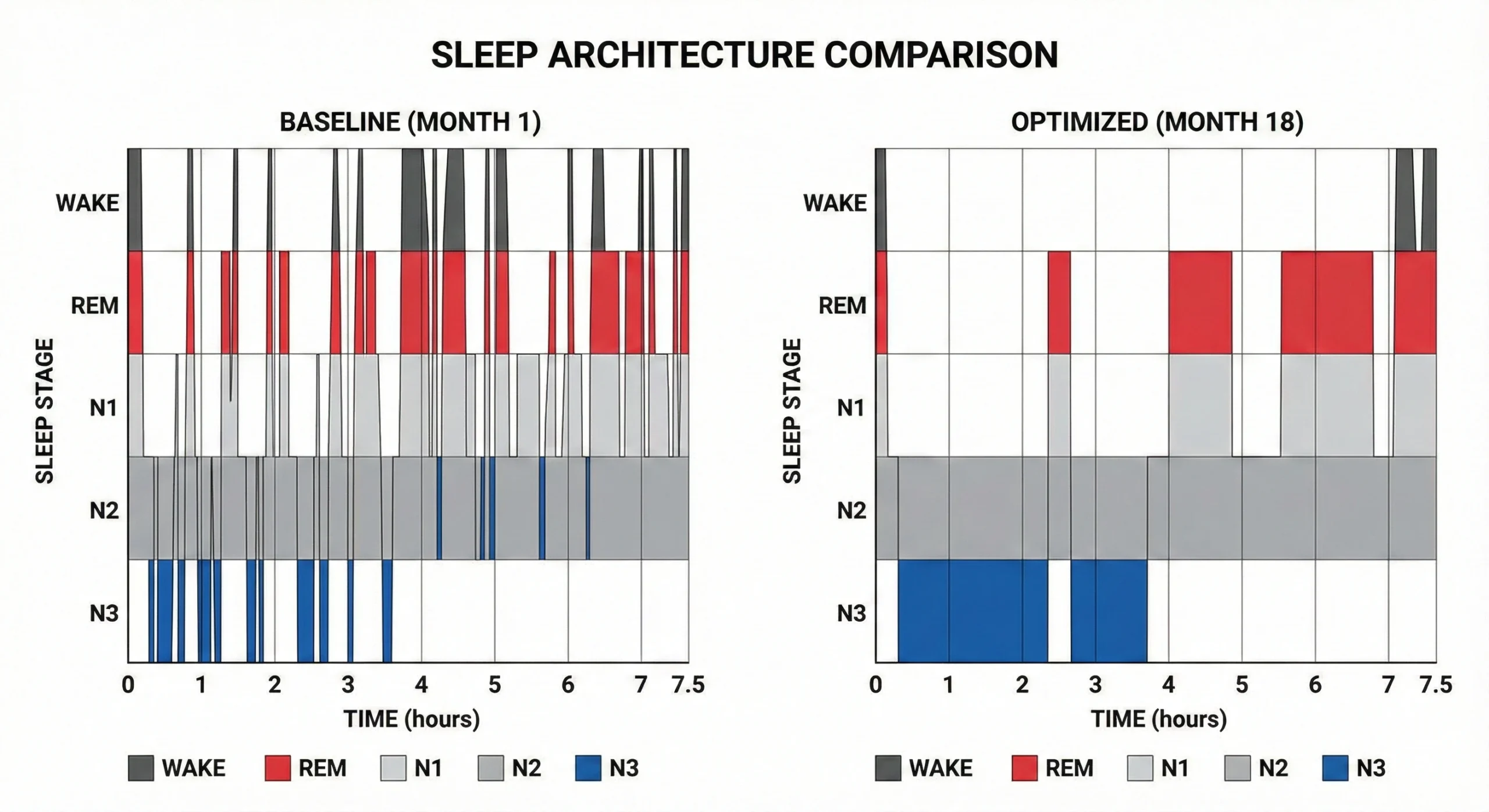

What I Learned From Tracking My Sleep Architecture for 18 Months

When I first started tracking sleep stages with a Whoop band, I thought it would confirm what I already knew: I wasn’t sleeping enough. What I discovered was far more nuanced — my problem wasn’t just duration, it was architecture.

The Shocking Baseline (What My Sleep Actually Looked Like)

Month 1 baseline data (averaging across 30 nights):

- Total sleep time: 6 hours 45 minutes

- Sleep efficiency: 76% (meaning I was in bed 8.5+ hours to get 6h45m of actual sleep)

- Deep sleep: 48 minutes (12% of sleep) — well below healthy range

- REM sleep: 68 minutes (17% of sleep) — also below healthy range

- Light sleep: 4 hours 29 minutes (66% of sleep) — disproportionately high

- Awakenings: 8-12 per night (that I was aware of)

What this told me: I wasn’t cycling properly through sleep stages. I was spending too much time in light N2 sleep, not enough in restorative deep and REM sleep. My sleep was fragmented — waking up 8-12 times meant I was constantly being pulled out of deeper stages back to light sleep.

The low sleep efficiency (76%) meant I was losing 2+ hours per night lying awake. If I was in bed from 11 PM to 7:30 AM (8.5 hours), I was only sleeping 6.75 hours. That’s a massive waste of time in bed.

The specific pattern I noticed:

- First cycle: I’d get 15-20 minutes of deep sleep (good), minimal REM

- Second cycle: 10-15 minutes deep sleep, 10-15 minutes REM

- Third cycle: 5-10 minutes deep sleep, 15-20 minutes REM

- Fourth cycle: Zero deep sleep, 20-25 minutes REM, then wake up

My deep sleep was okay in the first cycle but dropped off rapidly. I wasn’t getting those extended 30-40 minute deep sleep periods that should dominate early night. And because I was only completing 3-4 cycles before waking, I was missing the REM-rich late cycles entirely.

First Fixes — Environment and Circadian Timing

Months 2-3: Fixing the obvious problems

Based on the data, I identified two clear issues:

- Sleep fragmentation (too many awakenings pulling me out of deep stages)

- Insufficient total sleep time (only 3-4 cycles, missing late REM)

Changes implemented:

- Installed complete blackout curtains (measured with light meter: <0.5 lux)

- Dropped bedroom temperature from 70°F to 64°F (experimented and found 64°F was my sweet spot)

- Added white noise machine

- Started morning light exposure routine (30 minutes outdoor walking at 7 AM)

- Moved bedtime from 11:30 PM to 10:15 PM (targeting 7.5 hours instead of 6.75)

Results after 6 weeks:

- Total sleep time: 7 hours 15 minutes (gained 30 minutes)

- Sleep efficiency: 84% (major improvement — falling asleep faster, waking less)

- Deep sleep: 72 minutes (17% of sleep) — moved into healthy range

- REM sleep: 88 minutes (20% of sleep) — improved but still slightly low

- Light sleep: 4 hours 15 minutes (58% of sleep) — better distribution

- Awakenings: 3-5 per night — dramatic reduction

What changed in my sleep architecture:

- First cycle: Now getting 25-30 minutes of deep sleep (proper consolidation)

- Second cycle: 20-25 minutes deep, 15 minutes REM

- Third cycle: 10-15 minutes deep, 25 minutes REM

- Fourth cycle: Minimal deep, 30+ minutes REM

- Sometimes completing a 5th partial cycle with REM

The cooler temperature had the biggest impact on deep sleep consolidation. My brain could now sustain 25-30 minute blocks of slow-wave sleep instead of being pulled back to light sleep every 10-15 minutes.

The earlier bedtime added an extra cycle, giving me more REM exposure overall.

The Stubborn REM Problem (Months 4-6)

Even after these improvements, my REM sleep was stuck around 85-95 minutes. Better than baseline, but still below the 100-120 minute target for optimal cognitive and emotional function.

What I tried that didn’t work:

- Magnesium supplementation: No measurable change in REM

- Eliminating all screens 2 hours before bed: Helped sleep onset but didn’t increase REM

- Meditation before bed: Made me calmer but REM stayed the same

What actually worked — the thermostat experiment:

I read research suggesting that thermoregulation affects REM sleep specifically. Your body can’t regulate temperature normally during REM, so if ambient temperature is suboptimal, REM periods get shortened or skipped.

I experimented with different bedroom temperatures, tracking REM duration:

- 68°F: REM averaged 82 minutes

- 66°F: REM averaged 91 minutes

- 64°F: REM averaged 103 minutes

- 62°F: REM averaged 107 minutes, but I woke up uncomfortably cold and overall sleep quality dropped

The sweet spot: 64°F. At this temperature, I consistently got 95-110 minutes of REM without sacrificing comfort or deep sleep.

The mechanism makes sense: REM sleep lacks thermoregulation, so if the room is too warm or too cold, your brainstem receives distress signals that shorten or fragment REM periods. A cool but not cold environment allows extended, uninterrupted REM.

The Exercise Timing Discovery (Months 7-9)

Around month 7, I noticed an unexpected pattern in my data: on days I did intense resistance training in the late afternoon (4-5 PM), my deep sleep increased by 10-15 minutes, but my REM sleep decreased by 10-15 minutes.

Typical training day architecture:

- Deep sleep: 95-105 minutes (excellent)

- REM sleep: 85-95 minutes (slightly reduced)

Rest day architecture:

- Deep sleep: 75-85 minutes (good)

- REM sleep: 100-115 minutes (excellent)

This was fascinating — exercise was enhancing deep sleep (expected, supported by research) but apparently at the expense of REM. I dug into the research and found studies suggesting that intense exercise close to bedtime can suppress REM sleep in the subsequent night, possibly due to elevated core temperature and cortisol lingering into sleep.

My experiment: I shifted intense training from 4-5 PM to 2-3 PM on training days, keeping everything else constant.

Result:

- Deep sleep: 90-100 minutes (still excellent)

- REM sleep: 100-110 minutes (recovered)

The earlier timing allowed more recovery time before sleep, preventing the REM suppression while maintaining the deep sleep enhancement from exercise. This small schedule change optimized both sleep stages simultaneously.

Current Sleep Architecture (Months 15-18)

After 15+ months of systematic optimization and tracking, here’s where my sleep stabilized:

Averaged over 90 nights:

- Total sleep time: 7 hours 28 minutes

- Sleep efficiency: 88% (in bed 8h30m, sleeping 7h28m)

- Deep sleep: 92 minutes (20.5% of sleep) — solidly in healthy range

- REM sleep: 108 minutes (24% of sleep) — optimal

- Light sleep: 4 hours 8 minutes (55.5% of sleep) — healthy distribution

- Awakenings: 1-2 per night (usually just bathroom trip)

Typical night architecture now:

- Cycle 1 (first 90 min): 5 min N1 → 35 min N2 → 35 min N3 → 15 min REM

- Cycle 2 (90-180 min): 3 min N1 → 30 min N2 → 30 min N3 → 27 min REM

- Cycle 3 (180-270 min): 2 min N1 → 40 min N2 → 15 min N3 → 33 min REM

- Cycle 4 (270-360 min): 35 min N2 → 5 min N3 → 50 min REM

- Cycle 5 (360-448 min): 20 min N2 → 38 min REM → wake naturally

This is textbook sleep architecture — deep sleep front-loaded in first 2-3 cycles, REM increasing dramatically in cycles 3-5. The structure matches what polysomnography studies show for healthy adult sleep.

Subjective improvements that correlate with architecture changes:

- Physical recovery: I can train 4-5x per week intensely without overtraining symptoms (improved deep sleep = better physical restoration)

- Cognitive performance: Memory, focus, and creative problem-solving all measurably better (adequate REM = proper cognitive consolidation)

- Emotional stability: I’m significantly less reactive to stressors, better mood overall (REM’s emotional processing function working properly)

- Immune function: Haven’t had a cold or flu in 14 months (deep sleep enhances immune system)

The objective data improvements translated directly to quality of life improvements. This wasn’t placebo — the architecture optimization produced real functional benefits.

What Light Sleep Actually Does (It’s Not Just Filler)

Most people dismiss light sleep as “not real sleep” because it’s not as deep as slow-wave sleep or as interesting as REM. But N1 and N2 serve important functions and should comprise 50-60% of total sleep in healthy adults.

Stage N1 — The Transition State

N1 is the lightest sleep stage, the transition between wake and sleep. You spend very little time here in healthy sleep (less than 5% of total sleep time).

Characteristics:

- Brain waves shift from alpha (8-13 Hz, relaxed waking) to theta (4-7 Hz)

- Muscle tone decreases but movement still possible

- Easy to wake from — a small noise or touch will bring you back to waking

- Hypnic jerks (sudden muscle twitches) occur during N1 as muscle tone decreases

- You may not realize you were asleep if awakened from N1

Purpose: N1 is primarily transitional. Every sleep cycle begins with brief N1 as you shift from wake or lighter stages into consolidated sleep. It’s also the stage you enter momentarily during brief nighttime arousals before returning to N2.

Research using polysomnography shows that healthy sleepers spend 2-5% of night in N1, with more time in N1 indicating fragmented, poor quality sleep.

When N1 becomes problematic:

- Spending >10% of sleep in N1 suggests sleep fragmentation

- Frequent cycling back to N1 from deeper stages indicates environmental disruptions (noise, light, temperature) or sleep disorders (apnea, periodic limb movements)

Stage N2 — Consolidated Light Sleep

N2 is where you spend the most time — approximately 50-60% of total sleep. This is consolidated sleep, not just transition, and it serves real functions.

Characteristics:

- Sleep spindles: Brief bursts of rapid brain activity (12-16 Hz) lasting 0.5-2 seconds. These spindles are thought to play roles in memory consolidation and protecting sleep from external stimuli.

- K-complexes: Large, sharp waveforms that occur spontaneously or in response to environmental stimuli. They help maintain sleep by suppressing cortical arousal.

- Muscle tone further reduced

- Heart rate slows and becomes regular

- Body temperature drops

- Harder to wake than N1 but still relatively light sleep

Studies on sleep spindles demonstrate that spindle density correlates with intelligence measures and learning ability, suggesting N2 plays an active role in cognitive processing, not merely serving as transition to deeper stages.

Functions of N2 sleep:

- Memory consolidation: Sleep spindles appear to facilitate transfer of information from hippocampus to cortex for long-term storage

- Sensory gating: K-complexes help suppress responses to external stimuli, allowing sleep maintenance in moderately noisy environments

- Metabolic regulation: N2 sleep correlates with glucose metabolism regulation and insulin sensitivity

- Immune function: Cytokine production and immune cell activity regulated during N2

N2’s relationship to deep and REM sleep: N2 serves as the “default” sleep stage. Your brain cycles through N2 between deep sleep periods and before REM sleep. In later sleep cycles when deep sleep no longer occurs, you alternate between N2 and REM.

Why “Light Sleep” Isn’t Wasted Sleep

Many people see their sleep tracker showing 50-60% light sleep and think “I’m not getting enough deep/REM sleep.” But this distribution is normal and healthy.

The 50-60% N2 distribution is optimal, not problematic. What matters is absolute duration of deep and REM sleep, not their percentage of total sleep.

Example of healthy vs unhealthy with same light sleep percentage:

Person A — Healthy:

- Total sleep: 7.5 hours (450 minutes)

- Light sleep (N2): 60% (270 minutes)

- Deep sleep: 20% (90 minutes)

- REM: 20% (90 minutes)

Person B — Poor quality:

- Total sleep: 6 hours (360 minutes)

- Light sleep (N2): 60% (216 minutes)

- Deep sleep: 15% (54 minutes)

- REM: 20% (72 minutes)

Both have 60% light sleep, but Person A is getting adequate deep (90 min) and REM (90 min) in absolute terms. Person B’s percentages look similar, but absolute minutes of deep and REM are below healthy thresholds.

The takeaway: Don’t worry about light sleep percentage if your deep and REM sleep durations are in healthy ranges (80-120 minutes deep, 90-120 minutes REM for adults). Light sleep filling the remaining 50-60% of your sleep time is exactly what should happen.

How Sleep Changes From Infancy to Old Age

Sleep architecture isn’t static throughout life. The distribution of sleep stages changes dramatically from infancy through old age, with important implications for understanding what’s “normal” at different life stages.

Infant and Childhood Sleep Architecture

Infants (0-12 months): Newborn sleep is fundamentally different from adult sleep, dominated by REM and lacking the consolidated slow-wave sleep seen in adults.

- Total sleep: 14-17 hours per day (polyphasic — multiple sleep periods)

- REM sleep: 50% of sleep (8+ hours per day) — critical for rapid brain development

- Active sleep: Infants have “active sleep” and “quiet sleep” rather than fully developed NREM stages

- Sleep cycles: Only 50-60 minutes (much shorter than adult 90-120 min cycles)

Research on infant sleep shows that the extraordinarily high REM percentage supports synaptogenesis and neural pathway formation during rapid brain development.

Children (2-10 years): Sleep architecture gradually matures toward adult patterns but with much more deep sleep.

- Total sleep: 10-13 hours

- Deep sleep: 20-25% (2-3 hours per night) — far more than adults

- REM sleep: 25-30%

- Sleep cycles: 90 minutes by age 3-5, matching adult duration

The high deep sleep percentage in children supports physical growth (remember, growth hormone peaks during deep sleep) and the enormous learning demands of childhood.

Teenagers: Adolescent sleep undergoes significant changes, with biological shifts in circadian timing.

- Total sleep need: 8-10 hours (often not achieved due to social/school constraints)

- Deep sleep: 18-23% — starting to decline from childhood levels

- REM sleep: 23-25%

- Circadian shift: Natural sleep phase delays by 1-2 hours during puberty (biological preference for later sleep and wake times)

Research demonstrates that the circadian delay in adolescence is driven by hormonal changes during puberty, making it biologically difficult for teenagers to fall asleep before 11 PM-midnight, which conflicts with early school start times.

Adult Sleep Architecture (Peak Stability)

Young adults (20-40 years): Sleep architecture is relatively stable during this period, representing the “ideal” adult pattern referenced in most sleep research.

- Total sleep need: 7-9 hours

- Deep sleep: 15-20% (75-120 minutes)

- REM sleep: 20-25% (90-135 minutes)

- Light sleep: 50-60%

- Sleep efficiency: >85% in healthy individuals

This is the reference architecture most studies use as “normal healthy sleep.”

Middle age (40-65 years): Gradual changes begin, particularly in deep sleep.

- Total sleep: 7-9 hours (need doesn’t change, but achieving it becomes harder)

- Deep sleep: 12-18% — noticeable decline, especially after age 50

- REM sleep: 20-24% — relatively preserved

- Sleep efficiency: Often decreases to 80-85%

- More frequent awakenings

Studies on middle-age sleep show that slow-wave sleep declines approximately 2% per decade starting around age 30, with steeper decline in men than women.

Older Adult Sleep Architecture (Normal Aging Changes)

Older adults (65+ years): Sleep architecture changes significantly with normal aging, though these changes are often misunderstood as pathological.

- Total sleep: 7-8 hours (need slightly decreases, but not dramatically)

- Deep sleep: 5-15% — major decline, sometimes nearly absent

- REM sleep: 18-23% — relatively well-preserved compared to deep sleep

- Light sleep: 60-75% — increases as deep sleep decreases

- Sleep efficiency: 70-80% — more time awake during night

- Earlier circadian phase: Natural tendency to sleep and wake earlier

Why deep sleep declines with age: Research suggests this is due to reduced brain metabolic needs and decreased growth hormone secretion in older adults. It’s a normal aging process, not inherently pathological, though excessive decline may indicate neurodegenerative disease risk.

A crucial finding from longitudinal studies: while deep sleep decreases with age, this doesn’t necessarily mean older adults need less sleep or experience less cognitive impairment from sleep loss. The decline in deep sleep is compensated by increased light sleep duration, and total sleep need remains relatively constant.

Common misunderstandings:

- “Older adults need less sleep” — False. They need similar total sleep (7-8 hours) but achieve less deep sleep within that time.

- “Poor sleep is inevitable with aging” — Partially false. While architecture changes are normal, severe insomnia or very poor efficiency often indicates treatable conditions (sleep apnea, medication effects, depression).

Why Your Sleep Stages Might Be Disrupted

Even with adequate sleep duration, poor sleep architecture can leave you feeling unrefreshed. Here are the most common disruptors and their specific effects on sleep stages.

Alcohol — The REM Suppressor

Alcohol is one of the most problematic sleep disruptors, despite being commonly used as a “sleep aid.”

How alcohol affects sleep architecture:

- Sleep onset: Alcohol reduces sleep onset latency (you fall asleep faster)

- Deep sleep: Slightly increases in first half of night

- REM sleep: Severely suppressed, especially in first 2-3 cycles

- Second-half fragmentation: As alcohol metabolizes (usually 3-4 hours after consumption), sleep becomes fragmented with frequent awakenings

Research on alcohol and sleep demonstrates that even moderate alcohol consumption (2-3 drinks) 2-3 hours before bed reduces REM sleep by 20-30% and increases sleep fragmentation in the second half of the night.

Why this matters: You might “sleep” 8 hours after drinking but wake up feeling terrible because you missed much of your REM sleep and experienced fragmented light sleep after 3 AM. Your brain didn’t get the emotional processing and memory consolidation it needed.

My experience: I tracked my sleep for a month while occasionally having 2-3 drinks with dinner (finishing by 8 PM, bed at 10:30 PM). On drinking nights:

- REM sleep: 55-70 minutes (compared to usual 100-110 minutes)

- Sleep fragmentation: 6-8 awakenings (compared to usual 1-2)

- Deep sleep: Slightly elevated first half (85 min vs usual 75 min in first 3 hours), but overall similar

The REM suppression was dramatic and consistent. I stopped drinking alcohol entirely once I saw this data. The cognitive and emotional benefits of preserving REM weren’t worth the temporary relaxation from alcohol.

Caffeine — The Deep Sleep Reducer

Caffeine’s effects on sleep are dose and timing-dependent, but even afternoon caffeine can disrupt architecture hours later.

How caffeine affects sleep:

- Sleep onset latency: Increases (takes longer to fall asleep)

- Deep sleep: Reduced by 15-30% when caffeine consumed within 6 hours of bed

- REM sleep: Minimally affected in most studies

- Sleep efficiency: Decreases (more time awake during night)

Studies on caffeine timing show that caffeine consumed 6 hours before bedtime reduces deep sleep duration by approximately 16 minutes and total sleep time by 41 minutes.

The half-life issue: Caffeine has a 5-6 hour half-life. If you drink coffee at 4 PM (200mg caffeine), at 10 PM you still have 100mg active in your system. At 4 AM, you still have 50mg. This residual caffeine blocks adenosine receptors needed for deep sleep pressure.

My caffeine experiment: I tracked sleep across 3 different caffeine protocols:

- Coffee until 2 PM: Deep sleep averaged 82 minutes

- Coffee until 12 PM: Deep sleep averaged 93 minutes

- No caffeine after 10 AM: Deep sleep averaged 98 minutes

The difference between protocols 1 and 3 was 16 minutes of deep sleep — a 20% increase just from earlier caffeine cutoff. I now stop all caffeine by 11 AM to maximize deep sleep.

Temperature — The Architecture Regulator

Both bedroom temperature and core body temperature profoundly affect sleep architecture.

Optimal temperature ranges:

- Deep sleep: Requires core temperature drop of 2-3°F; works best in 60-67°F ambient temperature

- REM sleep: Impaired by temperatures outside narrow range (too hot or too cold); optimal around 64-68°F

Research shows that bedroom temperatures above 70°F significantly reduce slow-wave sleep and increase wakefulness, while temperatures below 60°F can fragment REM sleep due to impaired thermoregulation during REM.

My temperature experiments showed:

- At 70°F: Deep sleep 65 min, REM 85 min

- At 66°F: Deep sleep 88 min, REM 96 min

- At 64°F: Deep sleep 92 min, REM 108 min

- At 62°F: Deep sleep 94 min, REM 98 min (REM decreased due to cold discomfort)

The 64°F sweet spot optimized both stages for my physiology.

My Quest to Optimize Each Sleep Stage (Obsessive Experimentation)

After understanding sleep architecture theory, I became obsessed with optimizing each stage individually. This led to 6 months of sometimes ridiculous experiments, but I learned what actually moves the needle for each stage.

The Deep Sleep Enhancement Project (Months 10-12)

My deep sleep was already decent (85-95 minutes) but I wanted to push it higher to see if I’d notice further benefits.

Experiment 1: Pre-sleep sauna

- Protocol: 20 min dry sauna (170°F) ending 90 minutes before bed

- Theory: Temporary core temperature rise followed by cooling should deepen sleep

- Result: Deep sleep increased to 102 minutes (from 88 min baseline) on sauna nights

- Problem: Sauna before bed made me feel wired rather than relaxed. The benefit wasn’t worth the discomfort.

- Verdict: Works but impractical for daily use

Experiment 2: Glycine supplementation

- Protocol: 3g glycine 30 minutes before bed

- Theory: Glycine may lower core temperature and enhance slow-wave sleep

- Result: Deep sleep increased 8 minutes on average (93 min vs 85 min baseline) — modest but consistent

- Subjective: Fell asleep slightly faster, no grogginess

- Verdict: Small benefit, worth continuing

Experiment 3: Afternoon exercise intensity

- Compared: Rest days, moderate exercise (30 min walk), intense lifting (60 min)

- Result:

- Rest: 82 min deep sleep

- Moderate: 88 min deep sleep

- Intense: 97 min deep sleep

- Pattern consistent across 4-week trial

- Verdict: Intense afternoon exercise is highest-impact intervention for deep sleep

Experiment 4: Carb timing

- Compared: High-carb dinner vs low-carb dinner (keeping total calories equal)

- Theory: Higher insulin might promote deep sleep

- Result: No measurable difference (89 min vs 87 min)

- Verdict: Carb timing doesn’t affect my deep sleep

What actually worked for deep sleep:

- Bedroom at 64°F (15-20 min increase)

- Intense exercise 3-4 hours before bed (10-15 min increase)

- Glycine 3g (5-10 min increase)

- Total darkness (measured improvement when I blocked all LEDs)

Current deep sleep average: 95-105 minutes (21-23% of 7.5-hour sleep)

The REM Sleep Enhancement Project (Months 13-15)

REM was my stubborn problem. Even with good sleep environment and duration, I was stuck at 90-100 minutes when I wanted 105-120 minutes.

Experiment 1: Temperature fine-tuning

- Already covered above — 64°F was optimal for REM

- Going cooler (62°F) actually reduced REM, likely because being cold during REM (when thermoregulation is impaired) caused microarousals

Experiment 2: Sleep extension

- Extended target sleep from 7.5 hours to 8 hours

- Theory: REM is concentrated in later cycles, so more cycles = more REM

- Result: REM increased from 95 min to 112 min average

- Problem: Waking up after 8 hours felt groggier than after 7.5 hours

- Verdict: Extra REM wasn’t worth the sleep inertia from waking mid-cycle

Experiment 3: Eliminating all alcohol

- Baseline (occasional drinking, 1-2x per week): 94 min REM average across all nights

- After eliminating entirely: 106 min REM average

- The 1-2 drinking nights were dragging down my weekly average significantly

- Verdict: Biggest single intervention for REM

Experiment 4: Meditation before bed

- Protocol: 10 min guided meditation at 10 PM (30 min before bed)

- Theory: Reduced presleep arousal might enhance REM

- Result: No measurable change in REM duration, but sleep onset latency improved

- Verdict: Helps falling asleep, doesn’t affect REM

Experiment 5: Omega-3 supplementation

- Protocol: 2g EPA/DHA daily for 8 weeks

- Theory: Some research suggests omega-3s support REM sleep

- Result: REM increased from 98 min to 104 min over 8 weeks

- Confound: Hard to isolate from other factors

- Verdict: Possible modest benefit, continuing anyway for other health reasons

What actually worked for REM:

- Eliminating alcohol entirely (10-15 min increase)

- Bedroom at 64°F (8-12 min increase)

- Sleeping 7.5 hours consistently (vs 7 hours) — (15-20 min increase)

- Possibly omega-3s (5-8 min increase, less certain)

Current REM average: 105-115 minutes (23-25% of 7.5-hour sleep)

The Failed Experiments (What Didn’t Work)

Not everything I tried moved the needle. Here are the interventions that showed zero measurable effect on my sleep architecture:

Blue-blocking glasses:

- Wore after 8 PM for 4 weeks

- No change in any sleep metrics

- Possible reason: I’d already removed most bright light exposure after 8 PM, so glasses were redundant

Magnesium supplementation:

- 400mg magnesium glycinate nightly for 8 weeks

- No measurable change in deep sleep, REM, or sleep efficiency

- Subjectively felt slightly more relaxed, but objective sleep unchanged

- Note: This might work for people deficient in magnesium; I likely had adequate levels

White noise vs silence:

- Compared weeks with white noise machine vs earplugs/silence

- No difference in sleep architecture or efficiency

- Both worked fine because I’d eliminated actual noise sources

Weighted blanket:

- Used 20-lb blanket for 3 weeks

- No measurable effect on any sleep stage

- Felt cozy but didn’t improve sleep objectively

CBD oil:

- 25mg CBD oil nightly for 4 weeks

- Zero effect on sleep onset, architecture, or subjective quality

- Expensive placebo for me

Valerian root:

- 400mg before bed for 2 weeks

- No effect

The lesson: Most supplements and gadgets marketed for sleep have minimal effect if you’ve already optimized the fundamentals (light exposure, temperature, exercise, timing). They might help people with terrible baselines, but they don’t push already-good sleep to excellent sleep.

What to Do With This Information (Action Steps)

Understanding sleep architecture is fascinating, but what should you actually do with this knowledge?

Prioritize Total Sleep Time First

Before worrying about stage distribution, ensure you’re getting 7-9 hours (for adults) of opportunity for sleep.

Why: You can’t optimize architecture if you’re chronically short-sleeping. All stages require time. If you’re only sleeping 5-6 hours, you’re missing entire cycles.

Action: Calculate your ideal wake time (based on work/life) and work backward 7.5-8 hours to find target bedtime. Commit to being in bed at this time for 4 weeks to establish pattern.

Fix Environment for Deep Sleep

If you want to increase deep sleep specifically:

Temperature: Drop bedroom to 60-67°F (experiment to find your sweet spot, likely 64-66°F) Darkness: Install true blackout curtains, cover all LEDs Exercise: Add afternoon exercise (3-4 hours before bed), preferably resistance training or vigorous aerobic

Track: If using sleep tracker, monitor deep sleep percentage. Target 15-20% (75-120 minutes for 7-8 hour sleep).

Protect REM Sleep

If you want to increase REM:

Duration: Extend sleep by 30-60 minutes (REM is concentrated in final cycles) Alcohol: Eliminate or strictly limit to early evening (finish by 6-7 PM if bedtime is 10-11 PM) Temperature: Keep bedroom cool but not cold (64-68°F seems optimal for REM) Consistency: Maintain regular sleep schedule (REM is sensitive to circadian disruption)

Track: Monitor REM percentage. Target 20-25% (90-130 minutes for 7-8 hour sleep).

When to Worry About Sleep Architecture

Most people don’t need to obsess over sleep stages. But certain patterns indicate problems worth addressing:

Red flags:

- Deep sleep consistently <10% of total sleep

- REM sleep consistently <15% of total sleep

- Sleep efficiency <75% (spending much more time in bed than actually sleeping)

- Frequent cycling back to N1 (indicates fragmentation)

These patterns suggest either environmental issues (fixable) or potential sleep disorders (may need medical evaluation for sleep apnea, periodic limb movements, etc.).

When to see a sleep specialist:

- Excessive daytime sleepiness despite “adequate” sleep duration

- Loud snoring, witnessed breathing pauses (possible apnea)

- Inability to fall asleep or stay asleep despite perfect sleep hygiene

- Severe disruption of sleep architecture that doesn’t improve with environmental fixes

Understanding Sleep Architecture — Why It Matters

Sleep isn’t just “time spent unconscious.” It’s a precisely orchestrated sequence of brain states, each serving distinct biological functions.

Deep sleep restores your body physically — repairing tissue, strengthening immunity, consolidating physical skills, and clearing metabolic waste from your brain.

REM sleep restores your mind — consolidating memories, processing emotions, fostering creativity, and maintaining cognitive function.

Light sleep isn’t wasted time — it facilitates memory transfer, protects sleep from disruption, and regulates metabolism.

All three are essential. Optimizing sleep means ensuring adequate time in each stage, which requires both sufficient total sleep duration and proper sleep environment to allow uninterrupted cycling.

The hierarchy of importance:

- Total sleep time: 7-9 hours for adults (you can’t optimize what doesn’t exist)

- Sleep continuity: Minimize awakenings that fragment cycles

- Circadian alignment: Sleep at the right time for your biology

- Environment: Temperature, darkness, noise optimized for stage progression

- Lifestyle factors: Exercise, caffeine timing, alcohol avoidance

Master these five, and your sleep architecture will largely take care of itself.

SOURCES

Research citations are embedded throughout the article as hyperlinks to PubMed. Key studies referenced:

- Sleep stage distribution: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12530990/

- Sleep cycle composition across night: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28495359/

- Ultradian rhythms: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8346293/

- Growth hormone and deep sleep: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10984593/

- Cerebral blood flow in deep sleep: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23589831/

- Glymphatic system and sleep: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24136970/

- Deep sleep and motor learning: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15731310/

- Age-related decline in deep sleep: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15456295/

- REM brain activity patterns: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9242923/

- REM sleep behavior disorder: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23589645/

- REM and memory consolidation: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17053484/

- REM emotional processing: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22001045/

- REM and creativity: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19150898/

- Sleep spindles and cognition: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22894587/

- Infant REM and brain development: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21075238/

- Adolescent circadian delay: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25325467/

- Aging and deep sleep: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24799456/

- Alcohol and REM suppression: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23347102/

- Caffeine timing effects: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24235903/

- Temperature and sleep architecture: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31105512/

- Exercise and deep sleep: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28919335/