⚡ Quick Summary (TL;DR)

- 🧠 What is it: Your body’s master clock that controls sleep and energy.

- ⚠️ The Problem: Lack of morning sun + bright lights at night.

- 🛠 The Fix: Morning sunlight + Darkness at night.

- ⏳ Timeline: Takes 5–14 days to fully reset.

Why It Matters:

You can’t “hack” sleep with supplements if your timing is off. If you feel tired during the day but “wired” at night, your clock is shifted. Only light timing can fix this.

Your circadian rhythm is a 24-hour biological clock controlled by the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in your hypothalamus. This master clock coordinates sleep-wake cycles, hormone release, body temperature, metabolism, and virtually every physiological process in your body through predictable daily patterns.

Light exposure is the primary zeitgeber (time cue) that synchronizes your circadian rhythm to the external 24-hour day. Morning bright light advances your circadian phase (making you sleepy earlier), while evening light delays it (pushing sleep later). Melatonin onset — the evening rise of your sleep hormone — is the most reliable marker of circadian timing, occurring approximately 2-3 hours before natural sleep onset in darkness.

When your circadian rhythm is misaligned with your sleep schedule, you experience chronic fatigue, poor sleep quality, and metabolic dysfunction regardless of sleep duration. Understanding circadian biology is essential for optimizing sleep timing rather than just sleep quantity.

Want Better Sleep Stats?

Theory is good, but tools get results. See the exact stack (mask, tape, supplements) I use to get 2+ hours of Deep Sleep every night.

Open Sleep HubUnderstanding Your Body’s Internal 24-Hour Clock

Most people think circadian rhythm is just about sleep and wake times. It’s far more comprehensive than that. Your circadian rhythm is a master regulatory system that coordinates thousands of physiological processes across a roughly 24-hour cycle.

The term “circadian” comes from Latin: “circa” (around) and “diem” (day). It describes biological processes that repeat approximately every 24 hours, even in the complete absence of external time cues.

The Suprachiasmatic Nucleus (Your Master Clock)

Your circadian rhythm is controlled by approximately 20,000 neurons in a tiny brain region called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), located in the hypothalamus directly above the optic chiasm (where your optic nerves cross).

Why this location matters: The SCN sits right above where visual information from both eyes converges, allowing it to receive direct input about environmental light levels through a dedicated neural pathway called the retinohypothalamic tract.

Research using lesion studies in animals demonstrated that destroying the SCN completely eliminates circadian rhythms in sleep-wake cycles, hormone secretion, and body temperature regulation, proving it functions as the body’s master clock.

What the SCN does:

- Generates intrinsic ~24-hour rhythmicity (even without external time cues)

- Receives light information from specialized photoreceptors in your retina

- Synchronizes peripheral clocks throughout your body (in organs, tissues, and individual cells)

- Coordinates timing of hormone release (melatonin, cortisol, growth hormone)

- Regulates body temperature fluctuations across the day

- Controls sleep-wake propensity timing

The distributed clock system: While the SCN is the master clock, nearly every cell in your body contains clock genes (CLOCK, BMAL1, PER, CRY) that generate their own ~24-hour rhythms. Your liver has a clock, your muscles have clocks, your digestive system has clocks. The SCN synchronizes all these peripheral clocks to keep your body functioning as a coordinated system rather than a collection of independent oscillators.

Studies using bioluminescent reporters in mice show that individual cells throughout the body exhibit circadian oscillations in gene expression, but these peripheral clocks quickly desynchronize from each other without SCN coordination.

Think of it like an orchestra: individual musicians (peripheral clocks) can play their parts, but without a conductor (SCN), they fall out of sync and create chaos instead of music.

The Intrinsic Period (Why You Need External Cues)

Here’s something crucial: your circadian rhythm is not exactly 24 hours. It’s approximately 24 hours — typically between 24.1 and 24.3 hours for most people, with individual variation ranging from 23.5 to 25 hours.

Research isolating humans from all time cues (no clocks, no daylight, no schedules) in underground bunkers found that free-running circadian periods average 24.2 hours, meaning people naturally drift later each day without external synchronization.

Why this matters: Because your internal clock runs slightly longer than 24 hours, you need daily external cues (zeitgebers) to synchronize it to the actual 24-hour day. Without these cues, you’d gradually phase-delay — going to bed and waking up later and later each day.

Light exposure is the strongest zeitgeber, but others include:

- Meal timing

- Exercise timing

- Social interaction

- Temperature fluctuations

The practical consequence: If you live in modern environments with weak light cues (dim indoor lighting all day, bright screens at night), your circadian rhythm may not synchronize properly to the 24-hour day. This creates chronic circadian misalignment even if you maintain a consistent sleep schedule.

I experienced this firsthand when I worked in a windowless office. I kept a consistent 11 PM – 7 AM sleep schedule but felt constantly jet-lagged. My intrinsic period was probably 24.3 hours, and without strong morning light exposure, my body was trying to drift 20-30 minutes later each day while my alarm forced me awake at the same time. The result was perpetual social jet lag.

What Circadian Rhythm Controls (Beyond Sleep)

While sleep-wake cycles are the most obvious circadian rhythm, the SCN coordinates dozens of physiological processes with predictable 24-hour patterns.

Hormone secretion patterns:

- Melatonin: Rises in evening darkness (typically starting 2-3 hours before natural sleep time), peaks around 3-4 AM, declines toward morning

- Cortisol: Lowest around midnight, begins rising around 2-3 AM, peaks 30-45 minutes after waking (the cortisol awakening response), gradually declines through the day

- Growth hormone: Peaks during first deep sleep cycle (typically 1-2 hours after sleep onset)

- Thyroid hormones: Peak in late afternoon/evening

- Testosterone: Peaks in early morning (this is why morning erections occur)

Research mapping 24-hour hormone profiles demonstrates that nearly all hormones exhibit circadian rhythmicity, with disrupted rhythms associated with metabolic, cardiovascular, and psychiatric disorders.

Body temperature regulation: Your core body temperature isn’t constant — it fluctuates by about 1-2°F across 24 hours in a predictable pattern:

- Lowest point: 4-6 AM (around 97.5°F)

- Begins rising: 6-8 AM

- Peak: Late afternoon/early evening (around 99°F)

- Begins declining: Evening, facilitating sleep onset

This temperature rhythm is so tightly coupled to the circadian system that core body temperature minimum is used as a marker of circadian phase in research studies.

Cognitive performance patterns: Your brain doesn’t function identically throughout the day. Cognitive abilities follow circadian patterns:

- Alertness: Peaks mid-morning (9-11 AM) and early evening (6-8 PM), with afternoon dip (2-4 PM)

- Reaction time: Fastest in late afternoon

- Working memory: Best in late morning

- Declarative memory: Consolidation strongest during sleep, recall best in morning

Studies on circadian variation in cognitive performance show that cognitive tasks performed at the wrong circadian phase can show 20-30% performance decrements even in rested individuals.

Metabolic and digestive rhythms:

- Insulin sensitivity: Highest in morning, declining through the day

- Glucose tolerance: Better in morning than evening

- Digestive enzyme secretion: Timed to anticipate regular meal patterns

- Liver metabolism: Processes nutrients differently based on time of day

This is why eating the same meal at 8 AM versus 10 PM produces different metabolic responses — your body is biochemically different at different times of day.

How Light Exposure Controls Your Body Clock

Light is not just something that allows you to see. It’s the primary signal your brain uses to synchronize your circadian rhythm to the external 24-hour day.

The Special Photoreceptors (ipRGCs)

Your eyes contain specialized photoreceptors called intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs) that detect light specifically for circadian regulation, separate from the rods and cones used for vision.

What makes ipRGCs unique:

- They contain melanopsin, a photopigment that responds preferentially to blue light (460-480nm wavelength)

- They connect directly to the SCN via the retinohypothalamic tract

- They’re maximally sensitive to bright light (1,000+ lux) and relatively insensitive to dim light (<50 lux)

- They integrate light exposure over time rather than responding to brief flashes

- They can signal “daytime” even when your eyes are closed (if light is bright enough to penetrate eyelids)

Research on ipRGCs discovered that these cells remain functional in mice lacking rods and cones (completely blind), allowing circadian photoentrainment without vision. This explains why some blind people maintain normal circadian rhythms while others experience free-running rhythms — it depends on whether their ipRGCs are functional.

Why blue light specifically: The melanopsin photopigment in ipRGCs has peak sensitivity around 480nm (blue light). This matches the wavelength distribution of natural daylight but poorly matches incandescent bulbs (~2700K, minimal blue) and strongly matches LED screens and modern lighting (5000-6500K, rich in blue).

This is why screens at night are particularly problematic for circadian timing — they emit exactly the wavelength most effective at suppressing melatonin and delaying your circadian phase.

How Light Timing Affects Your Circadian Phase

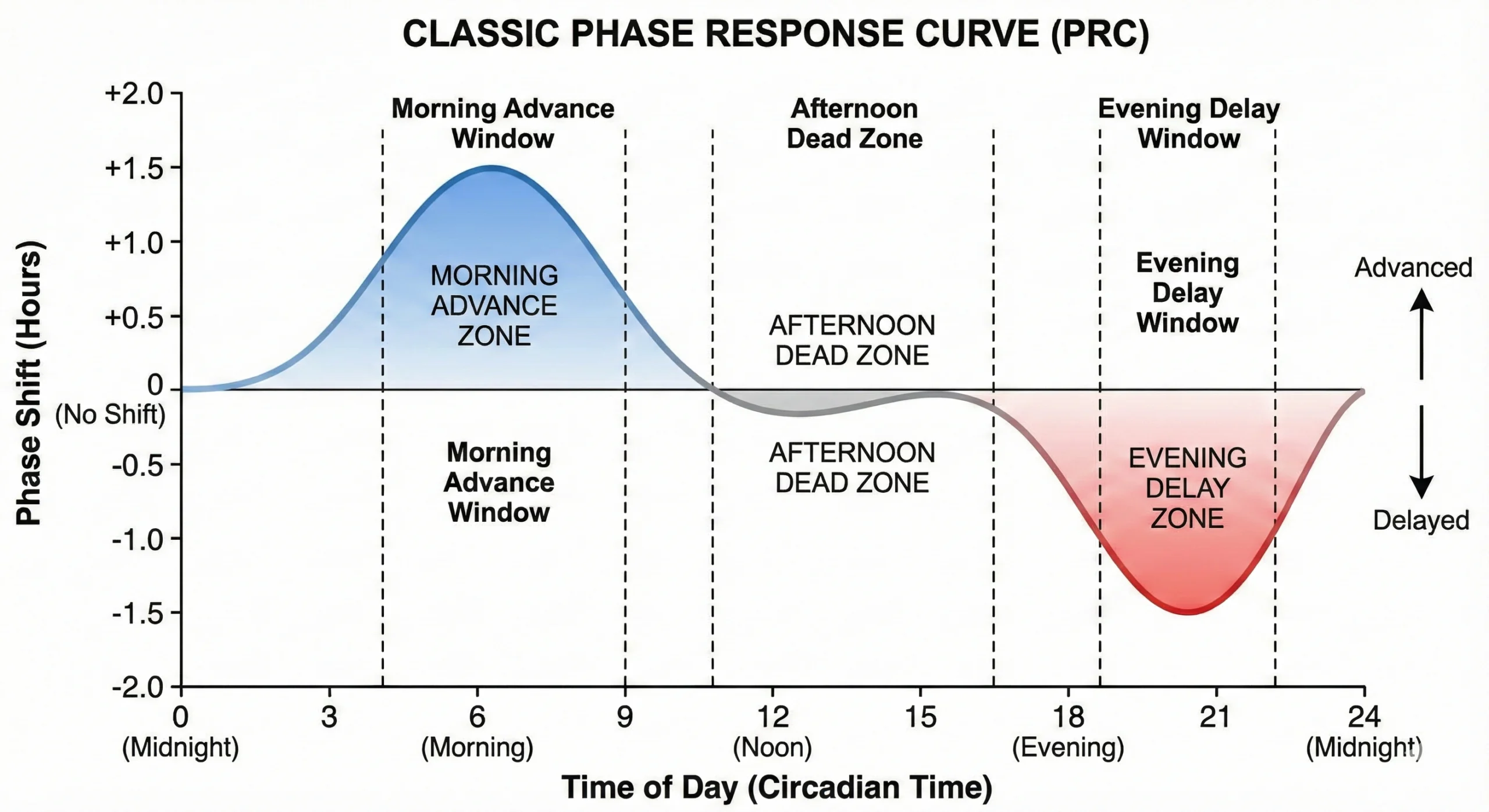

The same light exposure has completely different effects depending on when it occurs relative to your circadian cycle. This is called a phase response curve (PRC).

Morning light (first 1-3 hours after waking):

- Effect: Phase advance — shifts your circadian rhythm earlier

- Result: You feel tired earlier in the evening, wake up earlier the next morning

- Magnitude: 1-2 hour shift possible with consistent exposure

Afternoon/early evening light (6 hours before natural bedtime):

- Effect: Minimal phase shift

- Result: Maintains current rhythm but doesn’t significantly advance or delay

Late evening light (2-3 hours before natural bedtime):

- Effect: Phase delay — shifts your circadian rhythm later

- Result: You feel tired later, want to wake up later the next morning

- Magnitude: 30 minutes to 1.5 hours delay per evening of exposure

Middle of night light (2-6 AM):

- Effect: Complex — can either advance or delay depending on exact timing

- Result: Generally disrupts rhythm and fragments sleep

Studies mapping human phase response curves found that bright light exposure (>1000 lux) for 1-3 hours can shift circadian phase by 1-3 hours depending on timing, with morning light producing advances and evening light producing delays.

The critical windows:

- Phase advance window: First 2-3 hours after your core body temperature minimum (typically 6-9 AM for most people)

- Phase delay window: Evening, particularly 2-4 hours before your typical melatonin onset

Practical example: If you naturally feel tired at midnight but want to shift to a 10:30 PM bedtime:

- Do: Get bright light exposure at 7-8 AM (within 2 hours of waking)

- Don’t: Expose yourself to bright light after 8 PM

- Timeline: With consistent exposure, you’ll shift 30-60 minutes earlier per week

I used this exact protocol when I needed to shift from a natural 12:30 AM sleep time to 10:30 PM for a new work schedule. I bought a 10,000 lux light therapy lamp, used it for 30 minutes at 7 AM daily while eating breakfast, and dimmed all lights after 7:30 PM. Within 3 weeks, I was naturally tired by 10:30 PM instead of midnight.

Light Intensity Matters (Lux Measurements)

Not all light is equally effective at entraining circadian rhythms. Intensity matters enormously.

Lux levels in different environments:

- Sunny day outdoors: 50,000-100,000 lux

- Cloudy day outdoors: 10,000-25,000 lux

- Shade on sunny day: 5,000-10,000 lux

- Office with windows: 500-1,000 lux (if sitting near window)

- Typical office without windows: 200-500 lux

- Home lighting (LED/fluorescent): 200-400 lux

- Dim evening lighting: 50-100 lux

- Candlelight: 1-10 lux

- Moonlight: 0.1-1 lux

Research on light intensity and circadian effects shows that even relatively modest light exposure of 200 lux in the evening can suppress melatonin by 50%, while morning light needs to exceed 1,000 lux to produce significant phase-shifting effects.

The modern problem:

- We’re exposed to 100-500 lux all day indoors (1/20th to 1/100th the signal our biology expects during daytime)

- We’re exposed to 100-300 lux from screens and indoor lighting at night (100-300x the signal our biology expects at night)

This creates a “circadian twilight” where your SCN never receives strong enough “day” or “dark” signals to synchronize properly.

My light exposure measurement experiment: I wore a light meter for a week to track actual exposure:

- Average daytime exposure (9 AM – 5 PM): 380 lux (sitting in office near window)

- Average evening exposure (7 PM – 10 PM): 180 lux (home lighting + laptop screen)

- Maximum daytime exposure: 850 lux (sitting directly by window on sunny day)

These numbers were far below the 10,000+ lux needed for strong circadian entrainment. No wonder I had circadian misalignment issues.

After fixes:

- Moved desk directly adjacent to window: daytime average increased to 1,200 lux

- Added morning outdoor walks: 15-20 minutes at 15,000-30,000 lux

- Dimmed evening lights, used 2700K bulbs: evening exposure dropped to 40-60 lux

- Within 2 weeks, my natural sleep time shifted 90 minutes earlier without any willpower or effort

Duration and Timing of Light Exposure

It’s not just intensity — duration and timing matter for circadian effects.

Morning light requirements:

- Optimal: 30-60 minutes of 10,000+ lux within 2 hours of waking

- Minimum effective: 15-20 minutes of bright light (>1,000 lux)

- Timing: As soon after waking as possible produces strongest phase advance

Evening light avoidance:

- Critical window: 2-3 hours before natural bedtime

- Target: Reduce light to <50 lux where possible

- Duration: Longer dim light exposure produces less phase delay than brief bright exposure

Studies on light exposure duration found that continuous bright light exposure for 3-6 hours produces larger circadian shifts than brief pulses, but even 20-30 minutes can be effective if timed correctly and bright enough.

Practical protocols:

For early birds wanting to shift later:

- Avoid bright morning light (use sunglasses if outdoors before 8 AM)

- Get bright light exposure in late morning (10 AM – 12 PM)

- Allow moderate evening light exposure until 10-11 PM

For night owls wanting to shift earlier:

- Priority #1: Morning bright light within 1 hour of waking (non-negotiable)

- Priority #2: Dim lights after sunset (use warm-toned bulbs <2700K, dim to <50 lux)

- Priority #3: Avoid screens or use blue-blocking mode after 8 PM

For maintaining current rhythm:

- Consistent moderate-bright light during day

- Consistent dim light in evening

- Avoid middle-of-night light exposure

Understanding Melatonin’s Role in Sleep Timing

Melatonin is widely misunderstood as a “sleep hormone” that directly causes sleep. It’s more accurately described as a circadian timing signal that communicates “biological night” to your body.

What Melatonin Actually Does

Melatonin is produced by the pineal gland in your brain in response to darkness signals from the SCN. Its primary function is to signal the timing of biological night, not to directly induce sleep.

Melatonin’s roles:

- Circadian timing signal: Informs tissues throughout your body that it’s nighttime

- Sleep-permissive: Opens the “gate” for sleep to occur by reducing alerting signals, but doesn’t directly cause sleep

- Temperature regulation: Promotes heat dissipation from core to periphery, facilitating the temperature drop needed for sleep onset

- Antioxidant activity: Scavenges free radicals (a secondary function)

Research on melatonin administration shows that low-dose melatonin (0.3-0.5mg) given at appropriate circadian timing can shift circadian phase, while the same dose given at wrong times has minimal effect.

Melatonin vs adenosine (sleep drive):

- Adenosine: Builds up during wakefulness, creates sleep pressure, directly promotes sleep

- Melatonin: Rises in evening darkness, signals appropriate timing for sleep, enables sleep to occur

You need both for good sleep. High adenosine (strong sleep drive) without melatonin (wrong circadian timing) = difficulty falling asleep despite being exhausted. High melatonin (right circadian timing) without adenosine (no sleep drive) = feeling sleepy without actually sleeping deeply.

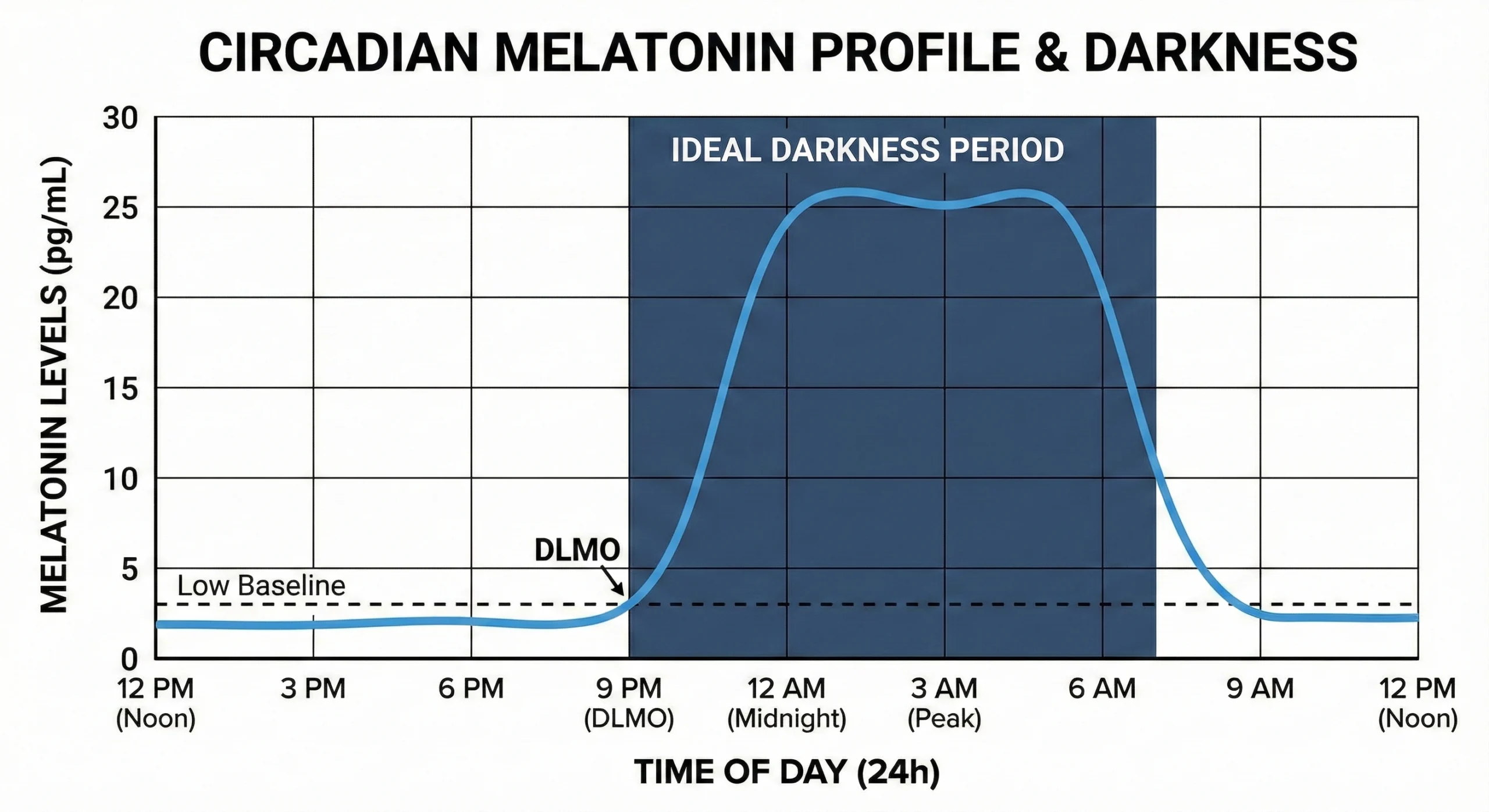

The Melatonin Curve (Normal Pattern)

In a healthy circadian rhythm, melatonin follows a predictable 24-hour pattern.

Typical melatonin profile:

- Daytime (6 AM – 6 PM): Undetectable or extremely low (<3 pg/mL)

- Dim light melatonin onset (DLMO): Begins rising around 8-10 PM (typically 2-3 hours before natural sleep time)

- Peak: Around 2-4 AM (20-30 pg/mL in darkness)

- Decline: Begins around 6-8 AM

- Morning: Returns to undetectable levels by 9-10 AM

The timing of DLMO (dim light melatonin onset) is the gold standard for assessing circadian phase in research. If your DLMO is at 9 PM, your circadian system considers 9 PM the beginning of biological night. If it’s at 11 PM, your biological night starts at 11 PM regardless of what the clock says.

Studies measuring DLMO across individuals found that DLMO timing varies by 3-4 hours between extreme early chronotypes and extreme late chronotypes, explaining why some people naturally feel tired at 9 PM while others aren’t sleepy until midnight.

What disrupts melatonin:

- Light exposure: Even 30-50 lux can suppress melatonin production

- Intense exercise: Late evening vigorous exercise can delay melatonin onset

- Stress: Elevated cortisol antagonizes melatonin

- Caffeine: Can delay melatonin onset even when consumed 6+ hours before bed

- Alcohol: Suppresses melatonin production and fragments its normal pattern

Melatonin Supplements (When They Help and When They Don’t)

Exogenous melatonin (supplements) can help in specific situations but is widely misused.

When melatonin supplements are effective:

- Circadian phase shifting: Low doses (0.3-0.5mg) taken 5-7 hours before DLMO can advance circadian phase

- Jet lag: Timed appropriately to destination time zone

- Blind individuals: Who lack light-based entrainment

- Shift work: To help adjust to rotating schedules

When melatonin supplements don’t help much:

- Chronic insomnia with normal circadian timing: If your DLMO is already aligned with desired bedtime, adding exogenous melatonin provides minimal benefit

- Strong sleep drive issues: If adenosine is low (sedentary lifestyle, frequent naps), melatonin won’t compensate

Research on melatonin for insomnia found that meta-analyses show modest effects on sleep onset latency (7-10 minutes reduction) in chronic insomnia, far less than fixing circadian misalignment through light exposure.

Dosing matters enormously:

- Physiological dose: 0.3-0.5mg (mimics natural nighttime levels)

- Common supplement dose: 3-10mg (10-30x higher than physiological)

- Problem: High doses can cause next-day grogginess, desensitize melatonin receptors, and disrupt normal rhythm

My melatonin experience: I tried 3mg melatonin nightly for a month when struggling with sleep. It helped me fall asleep 10-15 minutes faster but didn’t improve sleep quality and left me groggy in the morning. When I switched to fixing morning light exposure (30 minutes at 10,000 lux), I naturally felt tired 60 minutes earlier with no grogginess and better sleep quality. Light exposure addressed the root cause (circadian misalignment); melatonin was treating a symptom.

I now only use melatonin (0.5mg) for jet lag when traveling across 2+ time zones. Taken at the destination’s evening time, it helps shift my rhythm faster.

Understanding Your Natural Sleep-Wake Preference

Not everyone is meant to sleep 10 PM – 6 AM. Your chronotype — your natural circadian phase preference — is partly genetic and influences optimal sleep timing.

The Spectrum of Chronotypes

Chronotype exists on a spectrum from extreme early (“larks”) to extreme late (“owls”), with most people somewhere in the middle.

Distribution:

- Extreme early types (~10%): Natural DLMO around 7-8 PM, natural sleep 9 PM – 5 AM

- Moderate early types (~25%): DLMO around 8-9 PM, natural sleep 10 PM – 6 AM

- Intermediate types (~40%): DLMO around 9-10 PM, natural sleep 11 PM – 7 AM

- Moderate late types (~20%): DLMO around 10-11 PM, natural sleep 12 AM – 8 AM

- Extreme late types (~5%): DLMO around midnight or later, natural sleep 1-2 AM – 9-10 AM

Research on chronotype genetics identified that variants in clock genes (PER3, CLOCK, CRY1, among others) account for approximately 50% of chronotype variation, with the remainder due to age, sex, and environmental factors.

Age effects:

- Children: Tend toward earlier chronotypes

- Adolescents: Biological delay of 2-3 hours during puberty (teenagers naturally become night owls)

- Young adults (20s): Latest chronotypes

- Middle age: Gradual advance back toward earlier timing

- Older adults: Typically earlier chronotypes

This explains why forcing teenagers into 7 AM school start times creates chronic circadian misalignment — their biology is programmed for later sleep.

Social Jet Lag (When Your Chronotype Conflicts With Your Schedule)

Most people live with chronic circadian misalignment because their social/work schedule conflicts with their natural chronotype. This is called social jet lag.

Example: A natural night owl forced into early schedule:

- Natural chronotype: DLMO at 11 PM, natural sleep 1 AM – 9 AM

- Work requirement: Must wake at 6 AM (need to be in bed by 10 PM for adequate sleep)

- Problem: At 10 PM, their melatonin hasn’t even started rising. They’re forcing sleep 3 hours before biological night begins.

- Result: Difficulty falling asleep (lying awake 1-2 hours), chronic sleep deprivation on weekdays, “catching up” on weekends by sleeping until noon

Studies on social jet lag found that the magnitude of mismatch between chronotype and work schedule correlates with obesity, diabetes risk, depression, and cardiovascular disease.

Calculating your social jet lag:

- Note your midpoint of sleep on work days (e.g., bed 10:30 PM, wake 6:30 AM → midpoint 2:30 AM)

- Note your midpoint of sleep on free days (e.g., bed 1 AM, wake 9:30 AM → midpoint 5:15 AM)

- Calculate difference: 5:15 AM – 2:30 AM = 2 hours 45 minutes of social jet lag

Interpreting:

- <1 hour: Minimal misalignment

- 1-2 hours: Moderate misalignment (very common)

- 2 hours: Severe misalignment (associated with health consequences)

My social jet lag history: Before understanding this, I had 2.5 hours of social jet lag. I was forcing myself awake at 6 AM on weekdays (work requirement) but naturally sleeping until 9:30 AM on weekends. I felt constantly jet-lagged because I was living 2.5 hours off my biological time 5 days per week.

Once I understood this, I used morning light exposure to phase-advance my chronotype by about 1.5 hours over 6 weeks. I couldn’t shift all the way to 6 AM (my biology resisted that much), but I got to 7 AM feeling refreshed. I negotiated with work to start 30 minutes later, splitting the difference. My social jet lag dropped to 45 minutes — tolerable.

Can You Change Your Chronotype?

Your chronotype is partially genetic but can be shifted within limits using properly timed light exposure and other zeitgebers.

Shift potential:

- Genetic early types: Can potentially delay by 30-60 minutes with evening light

- Intermediate types: Can shift 1-2 hours in either direction with consistent light timing

- Genetic late types: Can advance by 1-2 hours with aggressive morning light

Research on chronotype flexibility found that weekend camping trips with natural light exposure advanced DLMO by an average of 1.2 hours in late chronotypes, showing substantial plasticity when light cues are strong.

How to shift your chronotype earlier (for night owls):

- Morning bright light: 30-60 minutes of 10,000+ lux within 1 hour of waking (non-negotiable)

- Evening light restriction: Dim all lights after 7-8 PM, avoid screens after 9 PM

- Consistent wake time: Wake at target time 7 days/week (including weekends)

- Avoid late-evening eating: Last meal 3 hours before target bedtime

- Timeline: Expect 15-30 minute shift per week with perfect adherence

How to shift your chronotype later (for early birds):

- Delay morning light: Don’t expose eyes to bright light for 2-3 hours after waking

- Evening bright light: 30-60 minutes of bright light at 7-9 PM

- Late-day activity: Exercise, social interaction, eating in evening

- Timeline: Similar, 15-30 minutes per week

Limits of shifting: You probably can’t turn an extreme owl into an extreme lark or vice versa. But you can shift intermediates by 1-2 hours in either direction with consistent effort.

How I Fixed My Circadian Misalignment (From Night Owl to Functional Morning Person)

I’m naturally a moderate-to-late chronotype. Left to my own devices (vacation, no alarm), I naturally fall asleep around 12:30-1 AM and wake around 9-9:30 AM. But modern adult life requires functioning at 6-7 AM. This created years of misalignment until I systematically addressed it.

The Baseline Problem (Why I Was Always Tired)

My pre-optimization pattern:

- Alarm at 6 AM for work (Monday-Friday)

- Would hit snooze 3-5 times, actually get up at 6:30-6:45 AM

- Feel terrible all morning, need 2-3 cups of coffee by 10 AM

- Start feeling alert around 11 AM-noon

- Evening energy peak 7-9 PM

- Not tired until midnight despite trying to sleep earlier

- Weekend: Sleep until 9:30-10 AM “to catch up”

I thought I was “just not a morning person” and needed to accept perpetual morning misery.

What was actually happening: My DLMO was probably around 11 PM, meaning biological night started at 11 PM. I was trying to force sleep at 10 PM (1 hour before biological night) and waking at 6 AM (before my biological morning). I was living 2-3 hours ahead of my circadian phase 5 days per week.

The weekend sleep-ins weren’t helping — they were perpetuating my delayed phase by allowing my natural chronotype to reassert itself, then Monday morning was even harder.

Attempting Willpower Fixes (What Didn’t Work)

Failed attempt #1: Going to bed earlier through discipline

- Forced myself into bed at 10 PM

- Lay awake 1-1.5 hours most nights

- Eventually fall asleep around 11:30 PM

- Still exhausted at 6 AM wake-up

- Result: Same total sleep, but wasted 1.5 hours lying in bed awake

Failed attempt #2: Sleep restriction

- Deliberately slept only 6 hours for a week thinking exhaustion would make me sleep earlier

- Became even more sleep-deprived

- Still couldn’t fall asleep before 11:30 PM

- Result: Compounded sleep debt without fixing timing

Failed attempt #3: Melatonin supplements

- Took 3mg melatonin at 9 PM for 2 weeks

- Fell asleep slightly faster (maybe 20 minutes)

- Woke up groggy

- Still felt out of sync with my schedule

- Result: Symptom management, not root cause fix

Why these failed: I was trying to force behavior change without addressing the underlying circadian misalignment. My SCN thought it was 8-9 PM when the clock said 10 PM. No amount of willpower could override biology.

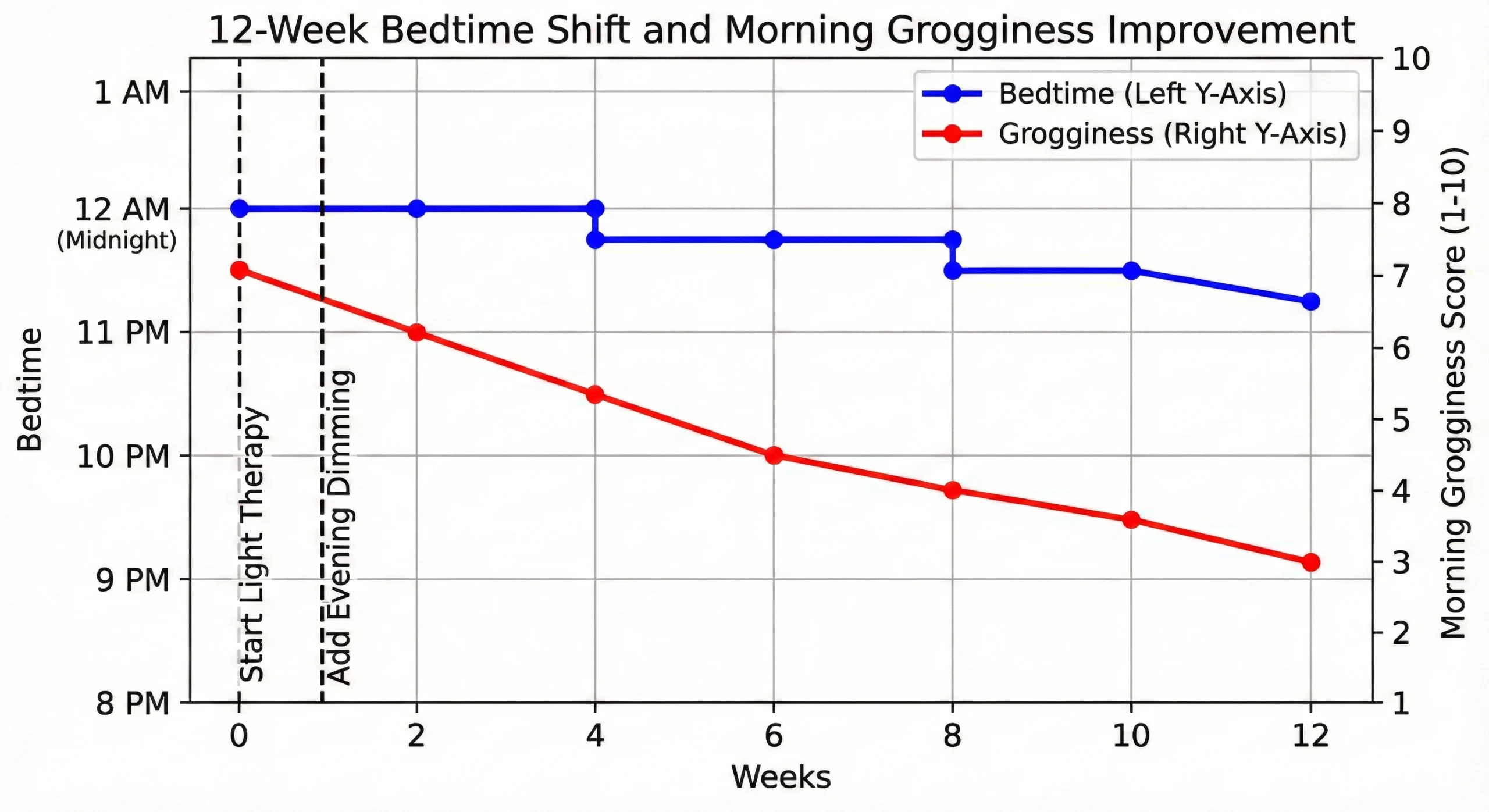

The Light Exposure Intervention (What Actually Worked)

After reading research on circadian photoentrainment, I realized I needed to shift my circadian phase through proper light timing, not force myself to sleep at the wrong circadian time.

Protocol implemented:

Morning (Phase advance strategy):

- Bought 10,000 lux light therapy lamp ($70 on Amazon)

- Used lamp for 30 minutes immediately upon waking (6:15 AM), positioned 12-18 inches from face while eating breakfast

- On sunny days: 20-minute outdoor walk at 6:30 AM instead of lamp

- Forced myself to wake at 6 AM even on weekends (hardest part)

Evening (Phase delay prevention):

- Installed f.lux on computer (auto-shifts to warm colors after sunset)

- Changed home lighting: replaced 5000K LED bulbs with 2700K warm bulbs, installed dimmers

- After 8 PM: dimmed all lights to minimum, avoided overhead lighting

- After 9:30 PM: no screens except e-ink Kindle, or phone with night shift on maximum

Additional timing cues:

- Breakfast within 30 minutes of waking (fed state signals daytime)

- No caffeine after 12 PM (was drinking coffee until 3 PM previously)

- Exercise moved to 4-5 PM (instead of 7-8 PM)

The Timeline of Shifts (Week by Week)

Week 1:

- Mornings brutal — waking at 6 AM felt like 4 AM would to most people

- Light exposure felt annoyingly bright, made me slightly nauseous at first

- Still not tired until 11:30 PM-midnight

- No measurable improvement yet

- Wanted to quit but committed to 4 weeks minimum

Week 2:

- Mornings slightly less terrible

- Started feeling natural sleepiness around 11 PM instead of midnight (30-minute advance)

- Still hitting snooze but only 1-2 times instead of 4-5

- Energy dip in afternoons reduced slightly

Week 3:

- Noticeable shift — feeling tired at 10:30 PM consistently

- Waking at 6 AM no longer felt like torture

- Morning alertness improved — needed less coffee

- Realized I was actually shifting when I caught myself yawning at 10:15 PM while watching TV

Week 4-6:

- Consolidated at new phase — naturally tired 10-10:30 PM

- Waking before alarm (5:50-6 AM) some mornings

- Morning energy good — felt alert by 7:30 AM

- Afternoon dip still present but less severe

Week 8-12 (Maintenance):

- New pattern stabilized

- Natural sleep time: 10:15-10:30 PM

- Natural wake time: 6-6:15 AM (often before alarm)

- Total shift: ~2 hours advance in circadian phase

- Energy throughout day much more stable

Objective verification: I used a sleep tracker (Whoop) that estimates circadian phase based on activity and sleep patterns. My estimated “biological midnight” shifted from 2:30 AM to 12:45 AM over the 12-week period — a 1 hour 45 minute advance.

Maintenance and Relapses

The shift wasn’t permanent without continued light exposure. I learned this during a winter work-from-home period.

What happened: I stopped my morning outdoor walks (too cold/dark) and stopped using my light therapy lamp (got lazy). Within 3 weeks, I noticed I was staying up later again (11 PM, then 11:30 PM). My morning wake-ups became harder.

I’d lost maybe 60 minutes of the advance I’d gained, drifting back toward my natural late chronotype.

The fix: Restarted morning light therapy lamp (15 minutes instead of 30, since I just needed maintenance not full shift). Within a week, back on track.

The lesson: Circadian phase shifting isn’t a one-time fix. If you’re working against your natural chronotype, you need ongoing light exposure to maintain the shift. It becomes automatic once you build the habit, but you can’t stop and expect the shift to persist.

Currently, I use my light therapy lamp 4-5 mornings per week (15-20 minutes while checking email). On weekends, I do morning outdoor walks. This maintains my shifted phase without requiring perfect adherence.

How to Optimize Your Sleep Timing (Evidence-Based Protocols)

Understanding circadian biology is interesting, but what should you actually do with this knowledge?

Determining Your Optimal Sleep Window

Your optimal sleep window is determined by three factors:

- Your natural chronotype

- Your required wake time (work, family, etc.)

- Your sleep need (7-9 hours for most adults)

Step 1: Identify your natural chronotype

Take a week of vacation with no alarm, no schedule, and natural light exposure. Go to bed when actually tired, wake naturally. After 3-4 days of “decompression,” your natural sleep pattern emerges.

Note:

- What time do you naturally feel tired?

- What time do you naturally wake?

- What’s your midpoint of sleep?

This reveals your genetic chronotype baseline.

Step 2: Calculate required sleep window

If you must wake at 6 AM and need 7.5 hours of sleep, your required bedtime is 10:30 PM.

Step 3: Assess the gap

If your natural chronotype says you’re tired at midnight but your required bedtime is 10:30 PM, you have a 1.5-hour misalignment that needs addressing.

Step 4: Decide on strategy

- Gap <30 minutes: Minimal intervention needed, just maintain consistent timing

- Gap 30 minutes – 1 hour: Phase shift achievable with moderate light exposure discipline

- Gap 1-2 hours: Phase shift possible but requires strict light timing for 6-8 weeks

- Gap >2 hours: Consider if wake time can be shifted (negotiate work hours), or accept some residual misalignment and optimize around it

Phase Advancing Protocol (For Night Owls/Delayed Schedules)

If you need to shift your circadian rhythm earlier:

Morning light exposure (Priority #1):

- Timing: Within 1 hour of target wake time

- Intensity: 10,000 lux for 20-30 minutes (light therapy lamp) OR 30-60 minutes outdoors

- Consistency: 7 days/week minimum for first 4-6 weeks

- Position: Light should hit eyes directly (can’t be off to side or behind you)

Research shows that morning bright light exposure produces phase advances averaging 1-2 hours after 1-2 weeks of consistent treatment.

Evening light restriction (Priority #2):

- Timing: Starting 3 hours before target bedtime

- Target intensity: <50 lux where possible, <200 lux maximum

- Practical steps:

- Dim overhead lights, use table lamps only

- Switch to 2700K warm bulbs (minimal blue light)

- Enable night shift/night mode on all devices

- Consider blue-blocking glasses after 8 PM if you must use screens

Wake time consistency (Priority #3):

- Wake at target time 7 days/week (including weekends)

- Use light alarm clock if helpful (gradual sunrise simulation)

- Get out of bed within 15 minutes of waking (don’t lie in bed)

- Expose to bright light immediately

Additional accelerators:

- Morning exercise (30+ minutes, outdoors if possible)

- Breakfast within 30 minutes of waking

- No caffeine after noon

- Evening temperature drop (cool bedroom, warm shower 90 min before bed)

Timeline expectations:

- Week 1-2: Minimal subjective change, maintain consistency despite difficulty

- Week 3-4: Notice natural tiredness 30-60 minutes earlier

- Week 6-8: Full shift consolidated, wake time feels natural

Phase Delaying Protocol (For Early Birds/Advanced Schedules)

If you need to shift your circadian rhythm later (less common need, but relevant for shift workers or early birds wanting later schedule):

Evening bright light exposure:

- Timing: 2-4 hours before current natural bedtime

- Intensity: 2,500-5,000 lux for 2-3 hours

- Method: Light therapy lamp or bright indoor lighting

Morning light avoidance:

- Wear sunglasses outdoors for first 2-3 hours after waking

- Keep indoor lighting dim in morning

- Gradually expose to bright light later in morning (9-10 AM instead of 6-7 AM)

Meal and activity timing:

- Delay breakfast by 2-3 hours

- Schedule exercise for evening (6-8 PM)

- Social activity in evening

Caution: Phase delaying is generally harder than phase advancing and can easily overshoot, creating later bedtime than intended. Monitor carefully.

Managing Extreme Circadian Challenges

Some situations create severe circadian disruption that requires specialized strategies.

Shift Work (The Circadian Challenge)

Shift work, particularly rotating shifts or night shifts, forces your circadian system to operate opposite to its natural programming. This creates profound health consequences.

Why night shift is biologically difficult:

Your circadian rhythm is programmed by millions of years of evolution to be awake during daylight and asleep at night. When you work night shifts, you’re asking your biology to function at its circadian nadir (lowest performance point).

Studies on shift workers show that chronic shift work increases risk of cardiovascular disease by 40%, diabetes by 30%, certain cancers by 20-40%, and psychiatric disorders by 30-50% compared to day workers.

Permanent night shift vs rotating shifts:

Permanent night shift:

- Can potentially adapt circadian rhythm to inverted schedule with strict light/dark timing

- Requires: Complete darkness during day sleep (blackout curtains, sleep mask), bright light during night work (10,000 lux), social isolation (no reverting to day schedule on days off)

- Reality: Most people can’t maintain this because social/family life requires some day activity

Rotating shifts:

- Worst possible scenario for circadian health

- Body never fully adapts to either schedule

- Each shift change requires 1-2 weeks of adjustment, then rotates again

- Chronic circadian misalignment is inevitable

Harm reduction strategies for shift workers:

If you can’t avoid shift work, minimize damage:

- Choose permanent over rotating shifts if possible

- Forward-rotating shifts (day → evening → night) are less disruptive than backward rotation

- Bright light during work (2,500+ lux) helps maintain alertness

- Complete darkness during sleep (blackout curtains + sleep mask + earplugs)

- Strategic napping (20-30 minutes before night shift)

- Melatonin timing (0.5-1mg before day sleep for night shift workers)

- Social support (family understanding that your sleep schedule is non-negotiable)

Consider switching careers: If you’re a permanent night shift worker experiencing health decline, seriously consider whether the job is worth the biological cost. Circadian disruption is not benign.

Jet Lag (Temporary Circadian Misalignment)

Jet lag occurs when you rapidly cross multiple time zones faster than your circadian system can adapt (roughly 1 hour per day).

Eastward travel (advancing circadian phase):

- Harder to adapt than westward travel

- You need to sleep earlier and wake earlier than your current rhythm

- Most people find this more difficult

Westward travel (delaying circadian phase):

- Easier to adapt

- You’re staying up later and sleeping later, which aligns with natural tendency to phase-delay

- Most people adjust faster

Jet lag mitigation protocol:

Before departure (3-4 days pre-travel if >3 time zones):

- Start shifting sleep schedule 30-60 minutes per day toward destination time

- Eastward: Earlier bedtime + morning light

- Westward: Later bedtime + evening light

During flight:

- Set watch to destination time zone immediately

- Sleep on plane only if it’s nighttime at destination

- Stay awake if it’s daytime at destination (use caffeine if needed)

Upon arrival:

For eastward travel:

- Seek bright light immediately upon morning arrival at destination

- No napping regardless of exhaustion (breaks circadian adaptation)

- Force yourself to stay awake until at least 9-10 PM destination time

- Consider 0.5mg melatonin at destination bedtime for first 2-3 nights

For westward travel:

- Avoid bright light in morning at destination

- Seek bright light in evening

- Stay active in evening to delay sleep

- Avoid early bedtime (delays adaptation)

My jet lag success story:

Last year I traveled from US East Coast to Central Europe (6-hour time difference eastward). I used this protocol:

Pre-travel: Shifted bedtime 1 hour earlier for 3 nights before flight (10 PM → 9 PM)

Flight: Red-eye departure at 10 PM, arrived 10 AM destination time. Forced myself to stay awake on plane despite exhaustion (used caffeine).

Arrival day: Went directly outside for 60-minute walk in bright sunlight at 11 AM destination time. Stayed active all day despite severe fatigue. Forced myself to stay awake until 10 PM destination time (felt like 4 PM home time). Took 0.5mg melatonin at 10 PM.

Day 2: Woke naturally at 6:30 AM (felt slightly groggy but not terrible). Morning walk in sunlight. By evening felt adjusted. Slept well without melatonin.

Day 3: Fully adapted.

Total adaptation: <48 hours for 6-hour eastward shift.

Previous trips without this protocol: 5-6 days of misery before feeling normal.

My Year of Circadian Self-Experimentation (What I Learned the Hard Way)

After successfully shifting my chronotype, I became obsessed with circadian optimization and ran a series of increasingly elaborate experiments on myself. Some worked brilliantly. Others failed spectacularly.

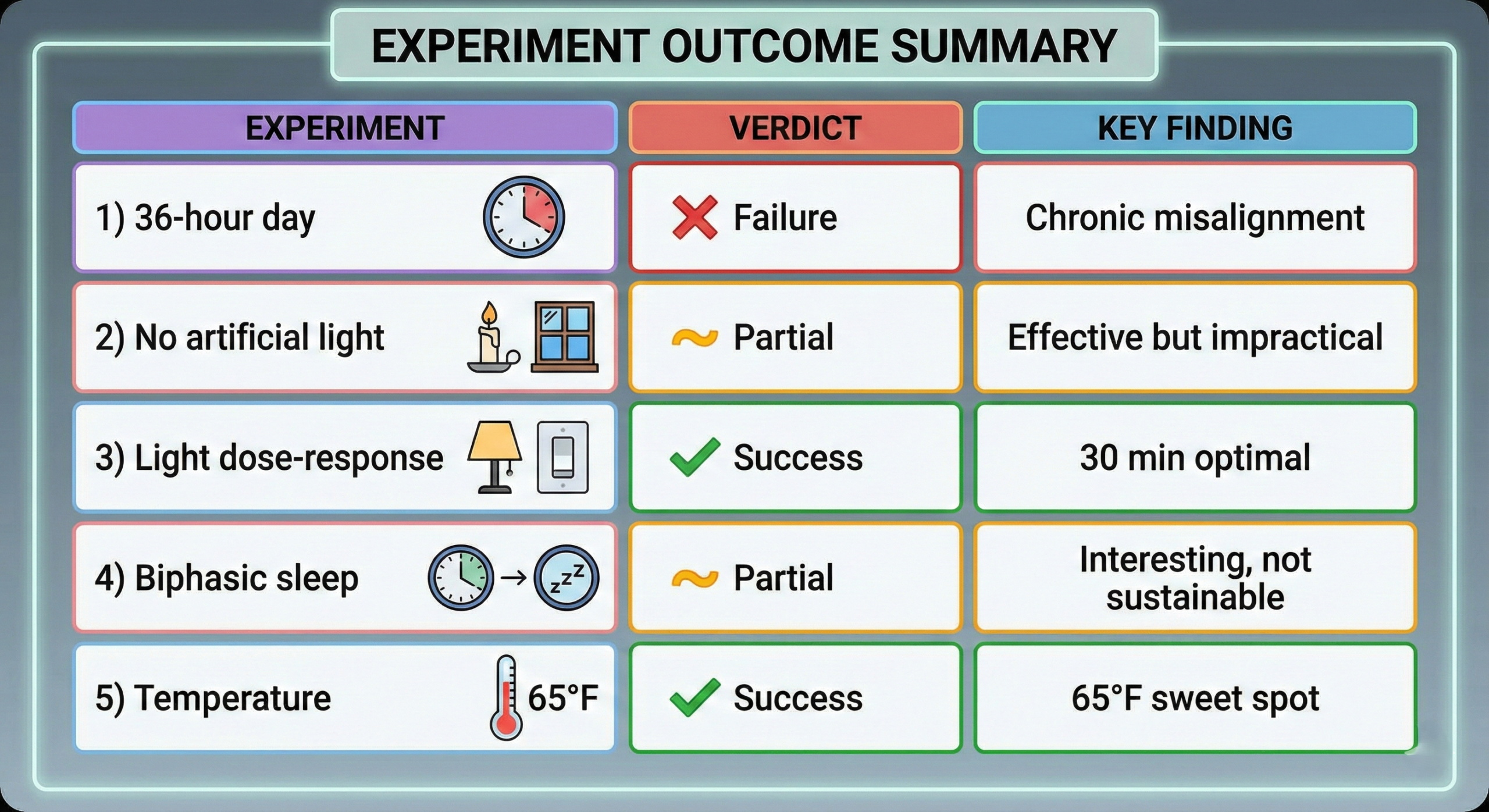

The 36-Hour “Day” Experiment (Failed)

I read about studies showing humans have intrinsic periods slightly longer than 24 hours and wondered: what if I lived on a 25-hour schedule? Would I feel more aligned with my natural rhythm?

Protocol:

- 10-hour sleep opportunity, 15-hour wake period

- Day 1: Bed 10 PM – 8 AM, awake 8 AM – 11 PM

- Day 2: Bed 11 PM – 9 AM, awake 9 AM – 12 AM

- Day 3: Bed 12 AM – 10 AM, awake 10 AM – 1 AM

- (Each day I’d shift 1 hour later)

Result after 2 weeks:

- Constant circadian confusion

- Sleep quality terrible (fragmented, never felt rested)

- Cognitive performance declined noticeably

- Mood became unstable

- Social life impossible (constantly at different times from everyone else)

Why it failed: While intrinsic period is ~24.2 hours, the 0.2-hour drift is normally corrected by daily light exposure. By deliberately ignoring 24-hour zeitgebers, I was creating chronic circadian misalignment rather than “aligning with natural rhythm.”

Lesson: Your intrinsic period doesn’t matter in practice. What matters is entraining to the actual 24-hour day using proper zeitgebers. Fighting the 24-hour cycle is a bad idea unless you’re living on Mars.

The “No Artificial Light After Sunset” Month (Partially Successful)

Inspired by camping research showing rapid circadian shifts with natural light only, I decided to eliminate all artificial light after sunset for 1 month.

Protocol:

- Sunset ~8 PM (summer month)

- After 8 PM: Only candles and fireplace for lighting

- No screens, no electric lights

- Reading by candlelight only

- Bed when felt tired

Results:

- Week 1: Felt bored and restless by 8:30 PM. Not tired yet. Went to bed at 9:30 PM out of boredom more than sleepiness.

- Week 2: Started feeling naturally tired around 9 PM. Sleep onset much faster (5-10 minutes instead of 20-30).

- Week 3-4: Natural bedtime stabilized at 8:45-9:15 PM. Waking naturally at 5-5:30 AM without alarm. Total sleep increased to 8-8.5 hours.

Unexpected benefits:

- Sleep quality dramatically improved (sleep efficiency 92% vs usual 85%)

- Morning alertness excellent

- Evening restlessness disappeared

- Felt more in tune with natural light/dark cycle

Downsides:

- Social isolation (couldn’t participate in evening activities)

- Productivity constraints (lost 2-3 evening work hours)

- Unsustainable in modern life

Current compromise: I still dim lights dramatically after 8 PM (candles/firelight-level in living areas) but allow screens for 1-2 hours with blue-blockers if needed for work. I don’t maintain the extreme sunset-darkness protocol but adopted the principle of dramatic light reduction in evening.

The Morning Light “Dose-Response” Experiment (Successful)

I wanted to quantify exactly how much morning light I needed for circadian entrainment, so I tested different durations.

Protocol: 4-week blocks of different morning light exposures, tracking sleep onset time and morning alertness

- Block 1: 10 minutes at 10,000 lux

- Block 2: 20 minutes at 10,000 lux

- Block 3: 30 minutes at 10,000 lux

- Block 4: 45 minutes at 10,000 lux

Results:

- 10 minutes: Minimal effect, natural bedtime stayed around 11:15 PM

- 20 minutes: Noticeable effect, bedtime shifted to 10:45 PM

- 30 minutes: Strong effect, bedtime 10:15 PM

- 45 minutes: Same as 30 minutes (no additional benefit)

Finding: 30 minutes appeared to be saturation point for my circadian response. Beyond that, more light didn’t produce further phase advance.

Current protocol: I use 25-30 minutes most mornings, occasionally cutting to 20 minutes when rushed. Below 20 minutes, I notice slight phase delay creeping back in.

The “Biphasic Sleep” Experiment (Interesting but Impractical)

I read historical accounts suggesting humans naturally sleep in two phases (first sleep + second sleep) before artificial lighting. Decided to test if this felt more natural.

Protocol:

- “First sleep”: 9 PM – 1 AM (4 hours)

- Awake period: 1 AM – 3 AM (2 hours of quiet activity by candlelight)

- “Second sleep”: 3 AM – 7 AM (4 hours)

- Total sleep: 8 hours

Results after 3 weeks:

- Sleep quality during each phase was excellent (deep and restorative)

- Middle-of-night wake period felt surprisingly natural after first week

- Used wake period for reading, journaling, meditation

- Morning alertness was good

- BUT: Completely incompatible with modern life

- Partner hated it (I was getting up at 1 AM)

- Work productivity suffered (split attention across weird schedule)

Interesting finding: During the 1-3 AM wake period, I felt calm and reflective in a way I never do during normal daytime. This might be the circadian nadir effect — reduced cortisol, no social demands, different mental state.

Verdict: Fascinating experiment, not practical for modern life. But it showed me that “solid 8-hour sleep” isn’t the only viable sleep architecture. Our ancestors likely did sleep differently.

The “Temperature Manipulation” Protocol (Highly Successful)

Curious about temperature’s circadian effects, I systematically manipulated bedroom temperature and tracked effects on sleep timing and quality.

Protocol: 2-week blocks at different bedroom temperatures, tracking sleep onset time, sleep architecture, and subjective quality

- Block 1: 70°F (my previous baseline)

- Block 2: 68°F

- Block 3: 65°F

- Block 4: 62°F

- Block 5: 60°F

Results:

- 70°F: Natural sleep onset 10:45 PM, deep sleep 75 min, REM 95 min

- 68°F: Sleep onset 10:35 PM, deep sleep 82 min, REM 100 min

- 65°F: Sleep onset 10:20 PM, deep sleep 92 min, REM 108 min (sweet spot)

- 62°F: Sleep onset 10:15 PM, deep sleep 95 min, REM 102 min (but felt uncomfortably cold)

- 60°F: Sleep onset 10:10 PM but frequent awakenings from cold discomfort, overall quality poor

Finding: 65°F was optimal for my physiology — cool enough to facilitate the temperature drop needed for sleep onset and deep sleep, but not so cold as to cause discomfort.

The circadian effect was real: cooler temperatures advanced my natural sleep time by 20-25 minutes (10:45 PM → 10:20 PM), independent of light exposure timing.

Mechanism: Core body temperature drop is a circadian signal for sleep onset. By pre-cooling my bedroom, I was facilitating the temperature drop that normally begins ~2 hours before sleep, effectively “pulling forward” my circadian sleep timing.

Current protocol: Bedroom at 64-65°F year-round (I adjust for seasonal variation slightly). This single intervention probably contributes 15-20% of my circadian phase advance.

Why Circadian Timing Matters for Long-Term Health

Circadian misalignment isn’t just about feeling tired. It has profound effects on metabolic health, immune function, cognitive performance, and disease risk.

Metabolic Consequences of Circadian Disruption

Your metabolism is under strong circadian control. Insulin sensitivity, glucose tolerance, and fat metabolism all vary across the 24-hour cycle.

Time-of-day metabolic effects:

- Morning: Highest insulin sensitivity, best glucose tolerance

- Evening: Insulin sensitivity 20-30% lower than morning, impaired glucose clearance

- Night: Metabolic processes shift toward storage rather than utilization

Research on circadian metabolism found that eating identical meals at different times of day produces different glycemic and insulinemic responses, with evening/nighttime meals causing higher and more prolonged glucose spikes.

Circadian misalignment and metabolic disease:

Studies on shift workers and people with social jet lag show:

- Type 2 diabetes risk: 30-40% increased risk with chronic circadian disruption

- Obesity: Correlation between social jet lag magnitude and BMI

- Metabolic syndrome: 2-3x higher prevalence in shift workers

One landmark study found that experimentally induced circadian misalignment (sleep timing shifted but meal timing fixed) caused pre-diabetic glucose levels in young healthy adults within 10 days.

Why this happens: When you eat or sleep at the wrong circadian time, your body’s metabolic machinery isn’t ready. It’s like trying to process a large meal when your digestive system is in “sleep mode” — the food gets processed inefficiently, leading to elevated glucose, increased insulin resistance, and fat storage.

Immune Function and Circadian Timing

Your immune system operates on a circadian rhythm. Immune cell production, inflammatory responses, and vaccine efficacy all vary by time of day.

Circadian immune patterns:

- Morning: Higher cortisol (anti-inflammatory state)

- Evening: Lower cortisol, increased inflammatory cytokine production

- Night: Peak immune cell trafficking and tissue repair

Research shows that vaccines administered in the morning produce 2-4x higher antibody responses than identical vaccines given in afternoon or evening, demonstrating strong circadian control of immune function.

Circadian disruption and infection risk:

Studies on shift workers find:

- 20-30% higher rates of common infections (colds, flu)

- Longer duration of illness

- Reduced vaccine efficacy

- Slower wound healing

The mechanism: chronic circadian misalignment dysregulates inflammatory balance and impairs immune cell function at times when they’re needed most.

Cognitive Performance and Mental Health

Circadian timing profoundly affects mood, cognition, and psychiatric health.

Depression and circadian misalignment: Research demonstrates strong links between circadian disruption and depression:

- Late chronotypes have 2-3x higher depression rates

- Social jet lag correlates with depressive symptoms

- Bright light therapy (circadian intervention) treats seasonal affective disorder and some major depression

Studies using light therapy for depression found that properly timed bright light exposure (10,000 lux for 30 minutes in morning) produces antidepressant effects comparable to SSRIs in some populations.

Why circadian alignment affects mood: Melatonin, serotonin, and other neurotransmitters involved in mood regulation are under circadian control. Misalignment disrupts these systems.

My personal experience with this: During my worst circadian misalignment period (2-3 hours social jet lag), I experienced persistent low-grade depression. Not severe clinical depression, but chronic low mood, anhedonia, and emotional flatness.

After fixing my circadian rhythm (primarily through morning light exposure), my mood improved dramatically within 3-4 weeks. I became noticeably more emotionally resilient, less reactive to stressors, and generally more optimistic. This was before any other life changes — purely from circadian realignment.

I didn’t realize how much circadian misalignment was affecting my mental state until it was fixed.

Understanding and Optimizing Your Circadian Rhythm

Your circadian rhythm is not a minor factor in sleep — it’s the foundation. Without proper circadian alignment, no amount of sleep duration, supplements, or sleep hygiene will produce truly restorative sleep.

The hierarchy of circadian optimization:

- Light exposure timing (highest impact)

- Morning bright light within 2 hours of waking

- Evening light restriction 2-3 hours before bed

- Consistent sleep-wake timing (second highest)

- Same wake time 7 days/week

- Same bedtime within 30-minute window

- Temperature regulation (moderate impact)

- Cool bedroom (60-67°F)

- Evening temperature drop facilitation

- Meal and exercise timing (supplementary)

- Meals aligned with circadian phase

- Exercise in afternoon/early evening

- Secondary zeitgebers (fine-tuning)

- Social interaction timing

- Caffeine timing

- Strategic melatonin use

Start with light: If you only fix one thing, fix your light exposure. Morning bright light + evening dim light will solve 70-80% of circadian misalignment issues.

Be patient: Circadian adaptation takes 1-3 weeks per hour of shift. A 2-hour phase advance requires 2-6 weeks of consistent protocol adherence.

Know your limits: You can shift your chronotype by 1-2 hours in either direction, but you probably can’t turn an extreme night owl into an extreme morning lark. Work with your biology, not against it.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the symptoms of a disrupted circadian rhythm?

The most common signs are feeling “tired but wired” at night, extreme difficulty waking up in the morning, brain fog mid-day, and digestion issues. If you rely on an alarm clock to wake up every single day, your rhythm is likely shifted.

How do I fix my sleep schedule ASAP?

The fastest way is “Morning Light anchoring.” Force yourself to wake up at your desired time (even if tired) and immediately get 20 minutes of sunlight. Do not nap. Repeat for 3 days. Your body will naturally start getting sleepy earlier.

Does melatonin help reset the clock?

Melatonin can help shift the clock if taken correctly (0.5mg–3mg about 2 hours before desired sleep), but it is not a cure. Light is a much stronger signal than supplements. Use melatonin only for short-term adjustments like jet lag.

Why do I wake up at 3 AM?

This is often due to a spike in cortisol or a drop in blood sugar. However, from a circadian perspective, it can mean your “sleep window” started too early or your light environment is not dark enough. Ensure your room is pitch black.

SOURCES

Research citations embedded throughout as hyperlinks to PubMed:

- SCN as master clock: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1117230/

- Peripheral clocks synchronization: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15226823/

- Human free-running period: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9230230/

- Circadian hormone rhythms: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8622535/

- Cognitive performance variation: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16796222/

- ipRGCs and circadian photoentrainment: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11818555/

- Light intensity and melatonin suppression: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21552190/

- Phase response curve to light: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8445957/

- Light duration and circadian shifts: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8776790/

- Melatonin phase-shifting effects: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9322266/

- DLMO and chronotype variation: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16687322/

- Melatonin for insomnia meta-analysis: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23691095/

- Chronotype genetics: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27494321/

- Social jet lag and health: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22396652/

- Camping and circadian shifts: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nihgov/28724878/

- Morning bright light phase advances: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15483477/

- Shift work health consequences: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16467543/

- Circadian timing and metabolism: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23633205/

- Experimental circadian misalignment: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24626061/

- Vaccine timing and immune response: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27071507/

- Light therapy for depression: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26580727/